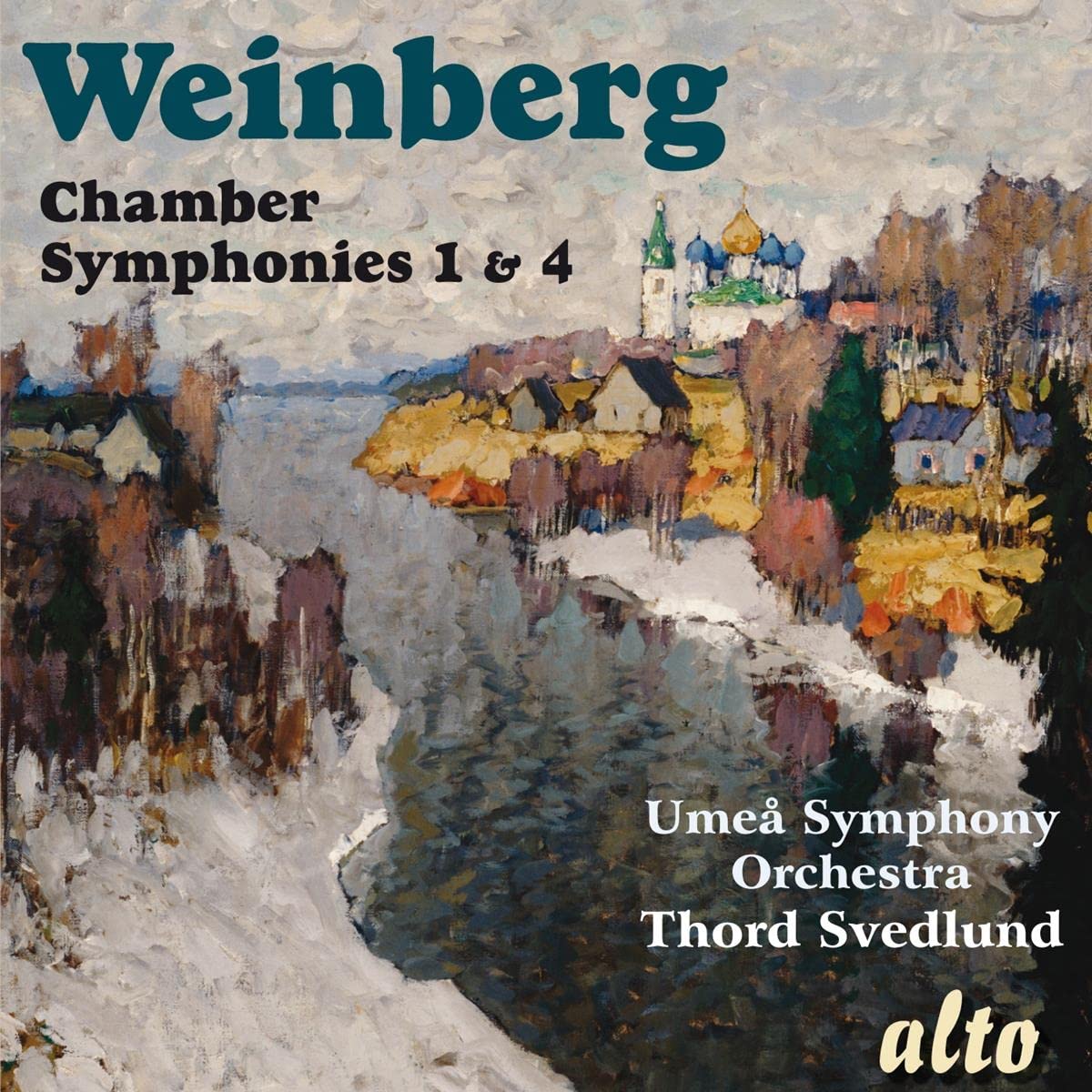

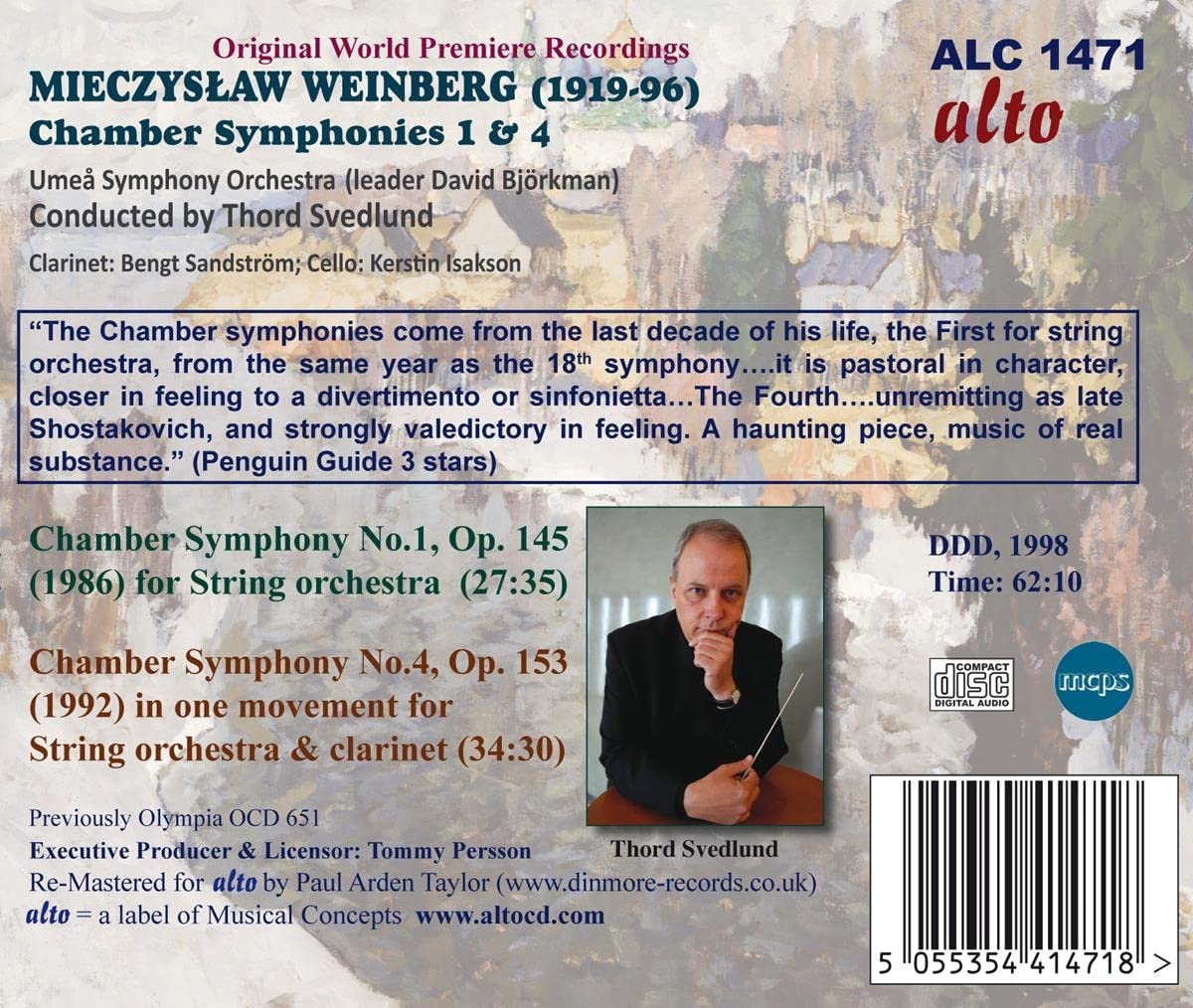

WEINBERG: Chamber Symphonies 1 & 4 – Umeå Symphony Orchestra, Thord Svedlund (CD + FREE MP3) ALTO

$ 7,99 $ 4,79

Original World Premiere Recordings

“The Chamber symphonies come from the last decade of his life, the First for string orchestra, from the same year as the 18th symphony….it is pastoral in character, closer in feeling to a divertimento or sinfonietta…The Fourth….unremitting as late Shostakovich, and strongly valedictory in feeling. A haunting piece, music of real substance.” (Penguin Guide 3 stars)

Chamber Symphony No.1, Op. 145 (1986)

for String orchestra (27:35)[1] I. Allegro 9:11[2] II. Andante 9:30[3] III. Allegretto 4:29[4] IV. Presto 4:25

Chamber Symphony No.4, Op. 153 (1992)

in one movement for string orchestra & clarinet (34:30)[5] Lento – 8:36[6] Allegro molto – Moderato – 7:16[7] Adagio – Meno mosso 10:33[8] Andantino – Adagissimo 7.56

TOTAL PLAYING TIME 62:10

MieczysławWeinberg (formerly mistakenly Moishe Vainberg) was born in Warsaw in 1919, the son of a composer and violinist at a Jewish theatre. When he was only ten he began his musical career there as a pianist and music director; two years later he started piano studies at the Warsaw Conservatory. After the German invasion of Poland in 1939 he was forced to flee the country and he went to the USSR, initially to Minsk. There he attended composition classes at the conservatory for two years, but when the Germans attacked the USSR in 1941 he had to flee again; he spent the next few years at the opera house in Tashkent, Uzbekistan. In the meantime his family had been murdered — burned alive — by the Germans.

In 1943 Weinberg sent the score of his newly completed First Symphony to Shostakovich, asking for an opinion of the work. Shostakovich arranged for him to receive an official invitation to Moscow — of especial value in the war years — and thus their close friendship was born. From the end of August 1943 until his death in 1996, Weinberg lived in Moscow, working as a freelance composer. From time to time he also made highly regarded appearances as a pianist — for instance, he performed alongside Galina Vishnevskaya, David Oistrakh and Mstislav Rostropovich at the première of Shostakovich’s Alexander Blok Songs and in his own now-famous Piano Quintet alongside the Borodins and with Oistrakh in his Moldavian Rhapsody for violin & piano (both: on ALC 1452).

Weinberg’s first wife belonged to a well-known Jewish family. Her father was the actor and director Salomon Mikhoels (his real name was Vovsi), the greatest Jewish actor in the Soviet Union, who was unforgettable as King Lear. Mikhoels was chairman of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee (JAC), which supported the work of a large writers’ collective. Under the leadership of Ilya Ehrenburg and Vasily Grossman, the latter organization prepared a ‘record of dishonour’ in which the atrocities committed by the Nazis against Jews in various countries were documented. The authors, however, had failed to predict that anti-Semitic persecution would reach terrifying levels in the Soviet Union as well. The respected Russian journalist Arkady Waxberg relates that publication of the ‘record of dishonour’ was forbidden; half of the contributors were arrested and either shot or sent to a gulag. A secret trial of the leaders of the JAC ended with the execution of 15 of its members on l2th August 1952. With this information, Waxberg also supplies a plausible explanation for the fate of Mikhoels, who was murdered by the secret police in Minsk on l3th January 1948. Weinberg, too, could have suffered a gruesome fate: towards the end of the Stalinist era, at 01.30am on 7th February 1953 (six months after the above-mentioned trial), he was arrested and imprisoned. It was with a sigh of relief that Shostakovich could write to his friend Isaac Glikman on 27th April 1953: ‘In the past few days M. S. Weinberg has returned home; he has informed me by telegraph.’ The date is significant (Stalin had died on 5th March and Weinberg’s release was probably a direct consequence), as is the fact that Shostakovich does not mention where Weinberg was returning from: such matters were not discussed openly. — So much for the hypocritical Communist legend of the equality of the peoples. A Jewish artist in the Soviet Union did not exactly enjoy an easy life.

Weinberg was an extremely productive composer with an output ranging from a Requiem to circus music. He had a (perhaps not entirely fashionable) inclination towards large-scale, epic music; in this respect Mahler and Prokofiev were important rôle models. His musical style was extremely varied, however, and his richly-coloured palette ranges from folk elements to dodecaphonic techniques. Folk-music elements were not only of Polish and Russian origin, but also Jewish and Moldavian (some of his ancestors had come from Moldavia).

The first two works in Weinberg’s opus list were both written before he left Poland: Lullaby for piano (1935) and String Quartet No.1 (1937). In an interview in 1994 the composer maintained that he had only turned to composition later on: ‘It was not until the outbreak of war that I began to devote myself seriously to composition, after the Germans had invaded Poland and I had fled to Minsk in the Soviet Union, where I began to study at the Minsk Conservatory. Until Hitler invaded the USSR, I studied there under Professor Vasily Andreyovich Zolotaryov, who was a pupil of Rimsky-Korsakov. There I completed a course in counterpoint and music history.’

In an interview for Sovietskaya Muzyka in the late 1980s Weinberg was asked why exactly he had given his Chamber Symphony No. 1 such a title, given that he had already composed his Second, Seventh and Tenth Symphonies for smaller forces — indeed for strings. His answer went as follows: ‘It’s true, I have gone slightly wrong. Of course the new symphony does not differ from the ones you mention in terms of the characteristics of its genre. You know, I had no desire to carry on with this series of high numbers. I recently also completed my Chamber Symphony No. 2… I repeat: neither in duration nor in character do the new symphonies differ from the second, seventh or tenth.’ The high numbers to which Weinberg mentioned naturally refer to the numbering of his ‘ordinary’ symphonies: he obviously wished to stop short of Myaskovsky’s total of no less than 27 symphonies. Even if we did not know of the composer’s pronouncement, the striking scale of the works recorded here would certainly reveal that the title ‘chamber symphony’ should perhaps not be taken too literally.

The Chamber Symphony No.1, Op.145, was completed in Moscow in August 1986. At this time Weinberg himself seems to have been unsure what to call the work. The original title in the manuscript has been pasted over; he subsequently wrote ‘Kamernaya simfoniya’, then deleted — and later reinstated — the word ‘Kamernaya’ (‘Chamber’). The underlying mood of this work, which is scored for string orchestra, is one of calm and peacefulness, and in structure it is classical. In the first movement, which is in sonata form — not even the repeat marks for the exposition are missing — the key of G major is only disturbed by a few dissonances. The music is slightly reminiscent of Prokofiev’s ‘Classical’ Symphony, although one might search in vain here for the latter work’s irony. The viola line in the coda distantly recalls a passage from the beginning of Shostakovich’s Tenth String Quartet, which is dedicated to Weinberg, and the movement ends indecisively.

The form of the second movement is original. Beginning with a sorrowful cantilena in B minor, it passes through a series of daring, ever more agitated modulations until, after a big climax, we arrive unexpectedly at a rapid, quiet passage in 3/8, like an eerie, encapsulated scherzo. After this ghostly interlude, however, the opening cantilena returns, and the movement ends quietly on the dominant.

The third movement, which is characterized by metrical variety, is an outstanding example of the appealing nature of many of Weinberg’s melancholy stow movements. In this movement in free song form, played con sordini, the melancholy is never obtrusive but is very tender, like a mournful puppy that wants to be consoled.

The work ends with a virtuoso rondo, the boisterousness of which forms the strongest contrast to the third movement. As in the first movement the basic key is G major, but it is not until the final bars that the composer’s cunning becomes evident: in fact G major has been the dominant all the time and so, at the end, we find ourselves in a joyous C major!

The Chamber Symphony No. 4, Op. 153, dedicated to the composer Boris Tchaikovsky, was composed in Moscow in the extremely short period between 30th April and l2th May 1992. The work is scored for string orchestra with the addition of a clarinet in A, which plays an extensive rôle, and a triangle which is used very sparingly (this may be something of an understatement, as it plays just four notes in the entire piece!). This chamber symphony was to be Weinberg’s penultimate work, and if we take this circumstance in conjunction with the work’s general mood, we might be tempted to describe it as a ‘summation of his life’ or ‘summation of his oeuvre’. Weinberg himself hated clichés of this kind and, as his view should be respected, we shall here proceed no further along this path.

On the other hand, we may well make another presumption, based on an indication provided by the composer himself: ‘I said to myself that God is everywhere. Since my First Symphony a sort of chorale has been wandering around within me…’ For obvious reasons, Weinberg could only make this fascinating comment after the collapse of the Soviet Union. (Moreover, towards the end of his life he had himself baptized.) Although it cannot be established with certainty, it could well be that this is the very chorale that we hear in the introduction to this chamber symphony. In fact the work begins with a whole series of psalmodic quasi-songs, not dissimilar to those found in Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov — and then, after 31/4 minutes, the clarinet makes its first appearance, joining the strings in a long, recitative-like passage, related in mood to the third movement of the First Chamber Symphony. A repetition of the ‘chorale’ then brings the section to a close.

Without a break we launch unexpectedly into the sudden triple forte of the very fast second section, an infectious scherzo, which proceeds almost without pause for breath until, quite late on, the clarinet begins a monologue which is then taken up first by a solo violin and later still by the cello. The section ends with a questioning tritone (F sharp — C).

The third section, which likewise follows with almost no break, is an Adagio which begins with a yearning, folk-like theme from the clarinet and continues with an impressive build-up from the strings; at the climax, the clarinet reappears to end the section with a tremolo/trill, crescendo.

The beginning of the last section is recitative-like, and the first triangle stroke is followed by an Andantino with a folk-like theme in the clarinet. The texture develops with ever greater artistry, and after a splendid clarinet cadenza the piece disappears in transfigured peace.

© Per Skans 1998

Violinist and conductor Thord Svedlund is a very experienced and versatile musician. He has studied in Sweden, USA and Holland, and has for many years worked as violinist in the Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra, the National Orchestra of Sweden. In 1991 he embarked on a conducting career that has earned him praise by critics and audiences alike. Thord Svedlund has conducted several of Sweden’s leading orchestras, including Gothenburg Symphony

Orchestra, Norrköping Symphony Orchestra, Gävle Symphony Orchestra, Swedish Chamber Orchestra and Umeå Symphony Orchestra. He has also worked as co-conductor with Neeme Järvi and Peter Eötvös. With the latter, he appeared in critically acclaimed performances of Charles Ives’ huge and demanding 4th Symphony in both Sweden and Germany. He has been invited to conduct in Shanghai, China. Thord Svedlund has recorded for radio and TV many times, and several CDs with music ranging from Bach and Haydn to contemporary Swedish composers. He has also now conducted four of Weinberg´s solo concertos on CD for Chandos.

The Umeå Symphony Orchestra is a young orchestra, having only played under its current name since the 1991-92 season. Its history extends much further; the orchestra was originally founded as a military band in 1841. In 1974, when the band also began to play for the newly founded Northern Opera of Sweden / Norrland Opera Company, it had become a regional woodwind and percussion ensemble, supplemented when necessary by a string section borrowed from Stockholm. In 1976 the orchestra began hiring its own string players and in 1978 it made its début performance as the Umeå Sinfonietta. Today the orchestra has 50 full-time musicians and regularly performs at Umeå’s many music festivals, as well as touring all over central and northern Sweden. It is still the orchestra of the Northern Opera of Sweden / Norrland Opera.

Fast Shipping and Professional Packing

Due to our longstanding partnership with UPS FedEx DHL and other leading international carriers, we are able to provide a range of shipping options. Our warehouse staff are highly trained to pack your goods exactly according to the specifications that we supply. Your goods will undergo a thorough examination and will be safely packaged prior to being sent out. Everyday we deliver hundreds of packages to our customers from all over the world. This is an indication of our dedication to being the largest online retailer worldwide. Warehouses and distribution centers can be located in Europe as well as the USA.

Orders with more than 1 item are assigned processing periods for each item.

Before shipment, all ordered products will be thoroughly inspected. Today, most orders will be shipped within 48 hours. The estimated delivery time is between 3-7 days.

Returns

The stock is constantly changing. It's not entirely managed by us since we are involved with multiple parties such as the factory and our storage. The actual stock can fluctuate at any time. Please understand it may happen that your order will be out of stock when the order is placed.

Our policy is valid for 30 days. If you haven't received your product within 30 days, we're not able to issue either a return or exchange.

You are able to return a product if it is unused and in the same condition when you received it. It must also still remain in the original packaging.

Related products

MUSIC CD

MUSIC CD

MUSIC CD