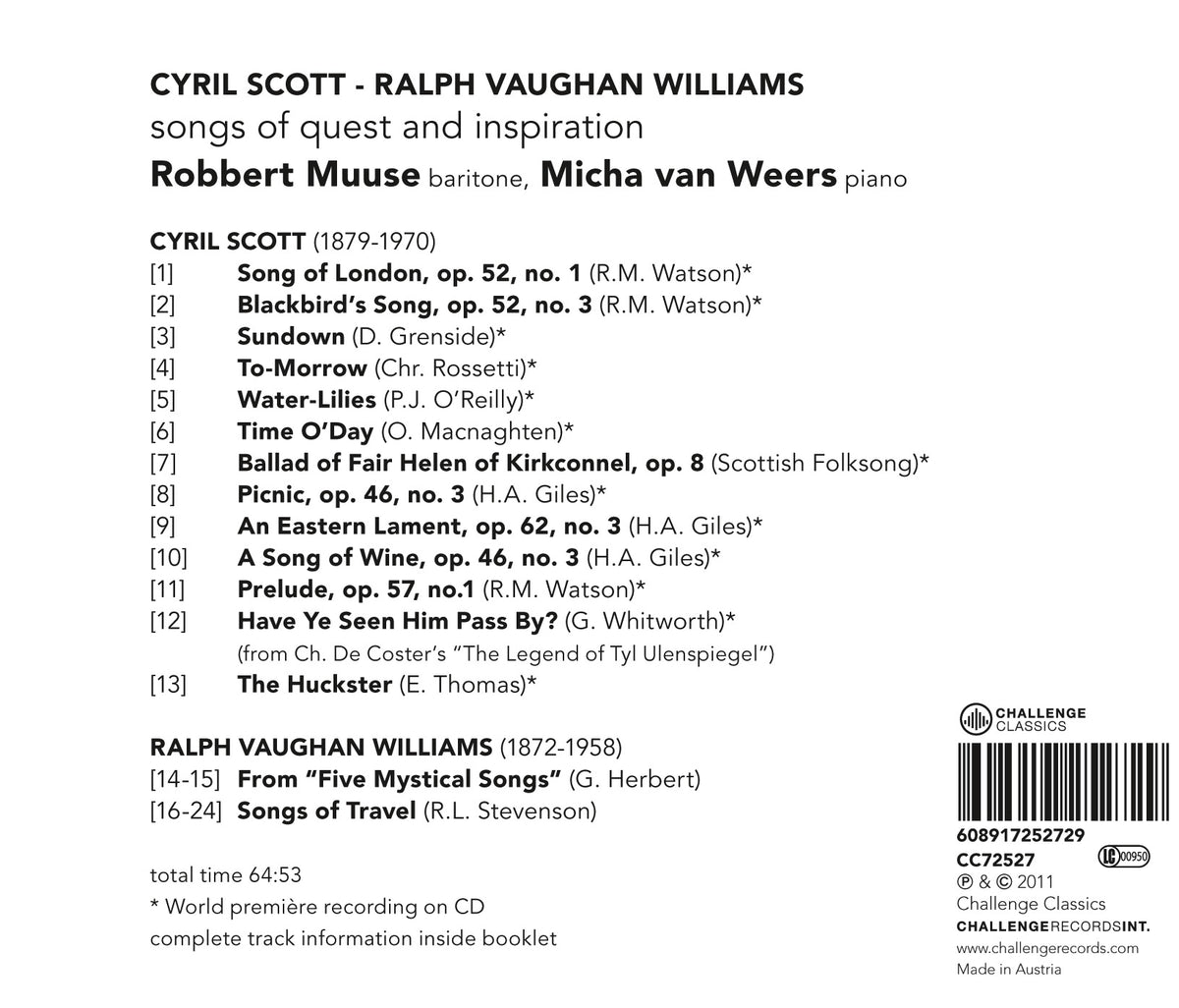

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS & SCOTT: SONGS OF QUEST AND INSPIRATION – ROBERT MUUSE & MICHAEL VAN WEERS CHALLENGE

$ 2,99 $ 1,79

Music history is often unfair to composers. Following his studies in Germany, Cyril Scott became known as the leader of the so-called “Frankfurt Group” of five British composers, including Percy Grainger and Roger Quilter, who “stood apart in outlook and education from the mainstream of the conservative British musical establishment”. Overall, he was a major figure in helping Britain to break away from Austro-Germanic musical hegemony. The famous conductor and composer Eugene Goossens even called him “The Father of Modern British Music;. Much to his own frustration, however, Scott became especially known as a successful composer of innumerable; short songs and piano pieces rather than for his serious compositions. By and large, he produced these;, as he called them, due to a contract that he signed with Elkin in 1904 and I suspect that the fact that he composed only four songs after 1930 had much to do with the ending of this arrangement. Ultimately, the main reasons for Scott’s dropping out from the British music establishment were his musical modernism and, in particular, his fascination with Occultism and Eastern philosophy, which increasingly influenced his musical style. By the 1940s, then, this cosmopolitan composer-pianist was everything but forgotten, though he would continue to compose and, indeed, to write numerous esoteric books, including his most famous Music: Its Secret Influence Throughout the Ages (1933), until the end of his life. No doubt, the revival of interest in Scott’s music during recent decades finally does justice to this remarkable, albeit somewhat eccentric, composer.

Conversely, for a long time in music history, the dominant image of Ralph Vaughan Williams has been that of an English nationalist ‘folksong’ composer. Yet, he never claimed that his collecting of English folksongs, which he began in 1903, liberated his muse and by 1918, in fact, he had largely abandoned composition based on folksong. Furthermore, ironically, the piece that overall established “the supposed high priest of the pastoral” as a musical spokesman of the nation, A London Symphony (1913), was a tribute to what was then the world’s largest city! Likewise, his A Pastoral Symphony (1921) was inspired originally by the landscape of wartime France and not, as generally understood, by that of peacetime England. Fortunately, since recent research has challenged many of the myths surrounding Vaughan Williams’ oeuvre, there now is emerging an image of a distinct modernist composer, who commanded a wide range of musical styles.

Besides the familiar, well-known repertoire, Robbert Muuse and Micha van Weers challenge themselves to continuously explore the field of unknown works, forgotten or even forbidden songs that they deem worthy to be re-discovered and performed as new. This research led to their present collection of approximately 80 songs by Cyril Scott, that have unjustly remained unknown to our generation.

CYRIL SCOTT

01. Song of London, op. 52, no. 1 01:42

02. Blackbird?s Song, op. 52, no. 3 02:57

03. Sundown 03:19

04. To-Morrow 02:02

05. Water-Lilies 01:52

06. Time O?Day (O. Macnaghten) (1919) 01:29

07. Ballad of Fair Helen of Kirkconnel, op. 8 03:58

08. Picnic, op. 46, no. 2 02:22

09. An Eastern Lament, op. 62, no. 3 02:07

10. A Song of Wine, op. 46, no. 3 02:34

11. Prelude, op. 57, no.1 01:42

12. Have Ye Seen Him Pass By? 02:47

13. The Huckster 01:45

RALPH VAUGHAN WILLIAMS

14. Five Mystical Songs: Easter 04:32

15. Five Mystical Songs: Love bade me welcome 05:09

16. Songs of Travel: The Vagabond 03:08

17. Songs of Travel: Let beauty awake 01:58

18. Songs of Travel: The Roadside Fire 02:22

19. Songs of Travel: Youth and Love 03:30

20. Songs of Travel: In Dreams 02:29

21. Songs of Travel: The infinite shining heavens 02:22

22. Songs of Travel: Whither must I wander 04:16

23. Songs of Travel: Bright is the ring of words 02:02

24. Songs of Travel: I have trod the upward and the downward slope 02:18

Fast Shipping and Professional Packing

Due to our longstanding partnership with UPS FedEx DHL and other leading international carriers, we are able to provide a range of shipping options. Our warehouse staff are highly trained to pack your goods exactly according to the specifications that we supply. Your goods will undergo a thorough examination and will be safely packaged prior to being sent out. Everyday we deliver hundreds of packages to our customers from all over the world. This is an indication of our dedication to being the largest online retailer worldwide. Warehouses and distribution centers can be located in Europe as well as the USA.

Orders with more than 1 item are assigned processing periods for each item.

Before shipment, all ordered products will be thoroughly inspected. Today, most orders will be shipped within 48 hours. The estimated delivery time is between 3-7 days.

Returns

The stock is constantly changing. It's not entirely managed by us since we are involved with multiple parties such as the factory and our storage. The actual stock can fluctuate at any time. Please understand it may happen that your order will be out of stock when the order is placed.

Our policy is valid for 30 days. If you haven't received your product within 30 days, we're not able to issue either a return or exchange.

You are able to return a product if it is unused and in the same condition when you received it. It must also still remain in the original packaging.

Related products

MUSIC CD

MUSIC CD

MUSIC CD

MUSIC CD