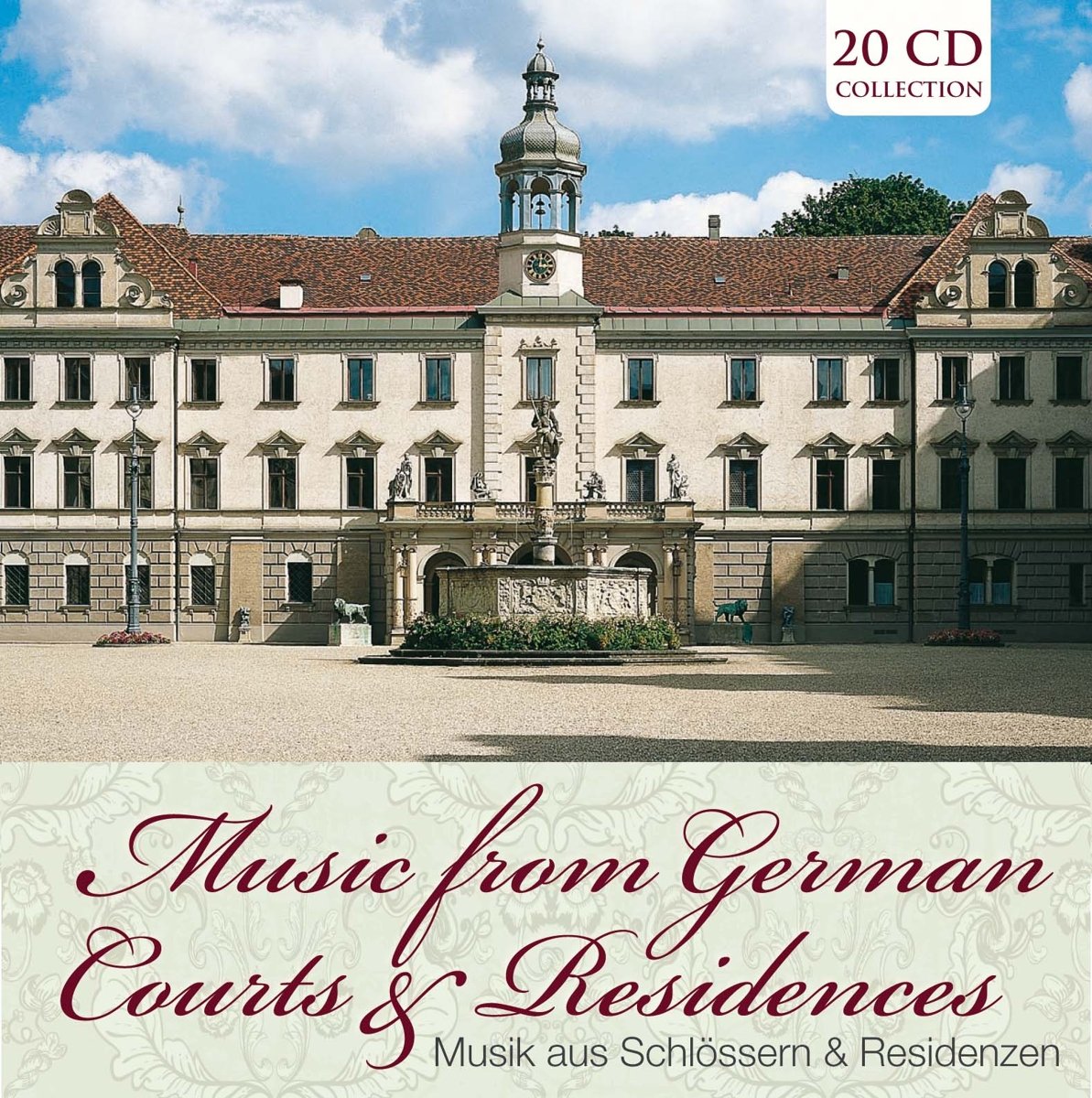

MUSIC FROM GERMAN COURTS AND RESIDENCES (20 CDS) DOCUMENT

$ 12,99 $ 7,79

Music From German Courts and Residences is a twenty CD box set of works from the 18th and 19th century, discovered at various royal German residencies. These technically brilliant stereo recordings of these very rare works, have been performed by pioneers of the art of historical performance, including Anner Bylsma, Dieter Klöcker and many others. This set was awarded the “Premio della Critica Discografica Italiana”.

Numerous invaluable manuscripts were found, many of which were presented to the public with these recordings for the first time. They revive the musical life in these castles and residences from a culturally exceedingly rich era. Notables could afford their own Court Opera and Orchestras and competed with each other, to hire the best artists, composers, and conductors of their time. In the collection presented here, soloists and ensembles of our time raise these musical discoveries to their proper rank of the highest quality. They bring to life the works of composers, whose names are rarely found in today’s concert programs: Cannabich, Rosetti, Fiala, Daser, Kalliwoda, Leffloth, Küffner, as well as father Leopold and son Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart found enthusiastic audiences in German castles. All of this can be heard in the recordings and read about in the extensive liner notes to this extraordinary CD box set.

Featuring performances by Jaap Schroeder, Anner Bylsma, Concerto Amsterdam, Consortium Classica and more!

Featured Soloists: Hermann Baumann, Horn; Christoph Kohler, Horn; Frans Vester, Flute; Pierre W. Feit, Oboe; Dieter Klöcker, Clarinet; Anner Bylsma, Violoncello

Consortium Classicum

Concerto Amsterdam: Jaap Schröder, Violin and Conductor

Münchner Philharmoniker. Marc Andreae, conductor

Capella Antiqua München. Konrad Ruhland, Leitung

Danzi-Quintett and others

CD 1: BADEN-WURTTEMBERG; DONAUSESCHINGEN

Andreas Späth: Nonet for 2 violins, viola, cello and double bass, oboe, clarinet, horn and bassoon

Allegro con spirito

Poco Adagio quasi Andante

Molto Vivace

Vivace

Joseph Fiala: Quartet for Oboe, violin, viola and cello

Allegro spirituoso

Menuetto

Andante

Allegro

Consortium Classicum

CD 2: BADEN-WURTTEMBERG; DONAUSESCHINGEN

Konradin Kreutzer: Quintet for piano, flute, clarinet, viola and cello

Allegro maestoso

Adagio

Scherzo molto vivace

Tempo di Polonaise

Konradin Kreutzer: Quartet for clarinet, violin, viola and cello

Allegro

Andante grazioso

Rondo Allegro moderato

Consortium Classicum

CD 3: THURN UND TAXIS

Franz Xaver Pokorny: Concerto in F major for 2 horns, strings and 2 flutes

Allegro

Larghetto poco andante

Finale: Presto assai

Franz Xaver Pokorny: Concerto in D major for flute and orchestra

Allegro molto

Adagio

Rondo

Karl Friedrich Abel: Concerto in B major for violin, oboe, clarinet and orchestra

Allegro

Adagio

Allegro ma non troppo

Concerto Amsterdam, Jaap Schroeder, director

CD 4: THURN UND TAXIS

Franz Anton Hoffmeister: Concerto in B major for clarinet and orchestra

Allegro

Adagio

Rondo: Allegro

Theodor Baron Von Schacht: Concerto in B major for clarinet and orchestra

Allegro – Tempo giusto

Adagio

Allegretto con variazioni

Concerto Amsterdam, Jaap Schroeder, director

CD 5: OETTINGEN – WALLERSTEIN

Antonio Rosetti (Franz Anton Rössler): Concerto in F major for horn and orchestra

Allegro vivace

Adagio

Rondo: Allegro

Joseph Reicha: Concerto in G major for cello and orchestra

Allegro

Adagio

Rondo: Allegretto

Concerto Amsterdam, Jaap Schroeder, director

CD 6: OETTINGEN – WALLERSTEIN

Johann Andreas Anion: Quartet in F major for horn, violin, viola and cello

Allegro moderato

Adagio

Rondo: Allegretto

Herman Baumann, Jaap Schroeder, Wiel Peeters, Dieter Klocker

Johann Andreas Anion: Quartet in D major, op 84 for flute, violin, viola and cello

Allegro assai

Poco adagio

Rondo: Allegretto

Frans Vester, Rainer Kussmaul, Jurgen Kussmaul, Anner Bylsma

Johann Georg Nisle: Septet in A flat major for flute, clarinet, horn, bassoon, violin, viola, cello and double bass

Allegro

Menuett

Adagio

Allegro vivace

Consortium Classicum

CD 7: WURZBURG

Friedrich Witt: Quintet in E-flat major, op. 6 for piano, oboe, clarinet, horn and bassoon

Allegro moderato

Adagio cantabile

Menuetto: Allegro molto

Finale: Allegro

Consortium Classicum

Joseph Küffner: Trio in A major, op. 21 for clarinet, viola and guitar

Andante con moto

Thema: Allegretto – Variationen – Allegro

Larghetto

Allegretto

Andante con variazioni

Polonaise

Dieter Klocker, Jurgen Kussmaul, Rolf Hockl

Joseph Frohlich: Serenade in D-Major for flute, clarinet, viola and cello

Larghetto

Allegretto

Andante con variazioni

Polonaise

Frans Vester, Dieter Klocker, Jurgen Kussmaul, Anner Bylsma

CD 8: WURZBURG

Friedrich Witt: Concerto in F major for 2 horns and orchestra

Allegro

Romanze

Rondo

Concerto Amsterdam, Jaap Schroder, director

Herman Baumann, Mahir Cakar, horn

Friedrich Witt: Symphony in A major

Adagio – Allegro vivace

Menuett

Andante

Finale Allegretto

Muncher Philharmoniker, Marc Andreae, conductor

CD 9: NURNBERG

Johann Matthäus Leffloth: Concerto in D major for harpsichord and violin

Andante

Allegro

Adagio

Bourrée en Rondeau

Anneke Uttenbosch, harpsichord; Jaap Scroeder, violin

Johann Matthäus Leffloth: Sonata in C major for viola da gamba and harpsichord

Adagio

Allegro

Adagio

Allegro

Veronika Hampe, Anneke Uitlenbosch, Jurgen Kussmaul, Anner Bylsma

Johann Christoph Vogel: Quartet in B major for clarinet, violin, viola and cello

Allegro non molto

Thema con variazioni

Adagio

Rondo: Allegro

Consortium Classicum

CD 10: NURNBERG

Johann Georg Heinrich Backofen: Sinfonia concertante in A major, op. 10 for 2 clarinets and orchestra

Allegro

(ohne Satzbezeichnung)

Rondo

Allegro moderate

Cantabile con variazioni

Concerto Amsterdam, Jaap Schroeder, conductor

Quintet in B Major for clarinet, violin, 2 violas and cello

Allegro moderato

Cantabile con variazioni

Consortium Classicum

CD 11: AUGSBURG

Leopold Mozart: Concerto in E flat major for 2 horns, strings and basso continuo

Allegro

Andante

La caccia: Allegro

Leopold Mozart: Sinfonia di camera in D major for horn, violin, 2 violas and basso continuo

Allegro moderato

Menuett

Andante

Allegro

Leopold Mozart: Sinfonia burlesque in G major for 2 violas, 2 violoncelli, bassoon and double bass

(ohne Bezeichnung)

Menuett

Andante Il Signor Pantalone

Harlequino

Leopold Mozart: Sinfonia da caccia in G major for 4 horns, strings, timpani and basso continuo

Allegro

Andante, più tosto un poco allegretto (a gusto dun eco)

Menuett

Concerto Amsterdam, Jaap Schroeder

CD 12: AUGSBURG

Franz Bühler (Pater Gregorius): Grande Sonate in E flat major for piano, clarinet, 2 horns, 2 violins, viola and cello

Allegro brillante

Romanze

Rondo: Presto

Consortium Classicum

Friedrich Hartmann Graf: Quartet Nr. 2 in G major for flute, violin, viola and cello

Allegro moderato

Adagio

Presto

Friedrich Hartmann Graf: Quartet No. 3 in C major for flute, violin, viola and cello

Andante moderato

Allegro

Finale: Non troppo presto

Franz Vester, Jaap Schroeder, Wiel Peeters, Anner Bylsma

CD 13: MUNICH

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Divertimento in B major, KV 196f (Anh. 227) for 2 clarinets, 2 horns and 2 bassoons

Allegro

Menuetto

Adagio

Menuetto

Finale: Andantino

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Divertimento in E-flat major , KV 196e (Anh. 226) for 2 clarinets, 2 horns and 2 bassoons

Allegro moderato

Menuetto

Romanze: Adagio ma un poco andante

Menuetto: Allegretto

Rondo: Andante

Franz Danzi: Sextet in E-flat major for 2 clarinets, 2 horns and 2 bassoons

Allegro

Andante

Menuetto: Allegro

Allegretto

Consortium Classicum

Dieter Klocker, Waldemar Wandel – clarinet

Werner Meyendorf, Niklaus Gruger – horn

Karl-Otto Hartmann, Eberhard Buschmann – bassoon

CD 14: MUNICH

Franz Danzi: Konzert F-Dur für Fagott und Orchester

Allegro

Andante

Polacca: Allegretto

Franz Danzi: Sinfonia concertante in B-flat major for clarinet, bassoon and orchestra

Allegretto

Andante moderato

Allegretto

Concerto Amsterdam, Jaap Schroeder, director

CD 15: MUNICH, BAYERISCHE HOFKAPELLE

Orlando Di Lasso: Missa Sexta, octo vocibus, ad imitationem Vinum bonura

Kyrie – Sanctus – Benedictus – Osanna – Agnus Dei

Timor, Domini, principium

Orlando Di Lasso: Kombt her zu mirspricht gottes son

Orlando Di Lasso: Magnificat sexti toni

Orlando Di Lasso: Schaff mir doch Recht in Sachen mein (ludica meDomine)

Orlando Di Lasso: Timor et tremor – Exaudi Deus

Orlando Di Lasso: A voi Gughelmo

Orlando Di Lasso: Sybilla Europea

Orlando Di Lasso: Vedi laurora

Orlando Di Lasso: O fugace dolcezza

Orlando Di Lasso: Matona mia cara

Orlando Di Lasso: La nuict froide et sombre

Orlando Di Lasso: Bicinium

Orlando Di Lasso: Der Tag ist so freudenreich

Orlando Di Lasso: Im Mayen hört man die hanen krayen

Orlando Di Lasso: Die Faßnacht ist ein schöne Zeit

Orlando Di Lasso: Am Abend spat beim kühlen Wein

Capella Antiqua, Munchen; Konrad Ruhland, direction

Hermann Baumann, horn

CD 16: MUNICH, BAYERISCHE HOFKAPELLE

Johannes De Fossa: Missa super theutonicam cantionem Ich segge ä dieu, Kyrie-Gloria

Ludwig Daser : Dominus regit me

Ludwig Daser : Benedictus Dominus

Ivo De Vento: Herrdein Wort mich getröstet hat

Jacob Reiner: Mane nobiscum Domine (Bleibe bei uns Herrdenn es will Abend werden)

Balduin Hoyoul: Wenn mein Stündlein vorhanden ist

Leonhard Lechner: Allein zu DirHerr Jesu Christ

Ludwig Senfl: Das Geläut zu Speyer (Nun kumbt hieher all)

Ludwig Senfl: Es wolltein Frau zum Weine gähn

Ludwig Senfl: Ich armes Käuzlein kleine

Ludwig Senfl: Fortuna – Nasciparimori

Ludwig Senfl: Es taget vor dem Walde

Ludwig Senfl: Patiencia muß ich han

Ivo De Vento: Frisch ist mein Sinn

Ivo De Vento: Ich weiß ein Maidlein

Ivo De Vento: So wünsch ich ihr ein gute Nacht

Leonhard Lechner: Nach meiner Lieb viel hundert Knaben trachten

Anton Gosswin: Am Abend spatlieb Brüderlein

Anton Gosswin: Schöne newe Teutsche Lieder,1581, Behüt euch Gott zu aller Zeit

Capella Antiqua, Munchen; Konrad Ruhland, direction

CD 17: MUNICH

Peter Von Winter: Sinfonia concertante in B-flat major, op. 20 for violin, viola, clarinet, bassoon, cello and orchestra

Allegro

Rondo: Allegro

(Allegro)

(Andante-Thema und Variationen)

Rondo

Movements 1-2:

Muncher Philharmoniker, Marc Andreae, conductor

Rainer Kussmaul, violin

Jurgen Kussmaul, viola

Gernot Schmalfuss, oboe

Dieter Klocker, clarinet

Karl-Otto Hartmann, bassoon

Anner Bylsma, cello

Movements 3-5

Concerto Amsterdam, Jaap Scroeder, director

Jaap Schroder, violin

Dieter Klocker, clarinet

Werner Meyendorf, horn

Karl-Otto Hartmann, bassoon

CD 18: MUNICH

Peter Von Winter: Septet in E-flat major, op. 10 for 2 violins, viola, cello, clarinets and 2 horns

Allegro moderato

Adagio

Menuetto: Allegro

Rondo: Moderato

Peter Von Winter: Octet in E-flat Major for violin, viola, cello, flute, clarinet, bassoon and 2 horns

Allegro

(ohne Satzbezeichnung)

(ohne Satzbezeichnung)

Consortium Classicum

Deiter Klocker, clarinet

Karl-Otto Hartmann, bassoon

Werner Meyendorf, Nikolaus Gruger, horn

Rainer Kussmaul, violin

Jurgen Kussmaul, viola

Anner Bylsma, cello

Jacques Holtman, violin

Frans Vester, flute

CD 19: MUNICH

Joseph Rheinberger: Nonett in E-flat major, op. 139 for flute, oboe, clarinet, horn, bassoon, violin, viola, cello and double bass

Allegro

Menuetto: Andantino

Adagio molto

Finale: Allegro

Danzi-Quintett

Frans Vester, flute

Marten Karres, oboe

Piet Honingh, clarinet

Adriaan van Woudenberg, horn

Brian Pollard, bassoon

with:

Jaap Schroeder, violin

Wiel Peeters, violin

Anner Bylsma, cello

Anthony Woodrow, double bass

CD 20: MUNICH

Karl Cannabich: Divertissement concertante in F major for 2 violins and orchestra

Adagio

Allegro con spirito

Andante sostenuto

Allegro

Andante

Allegro

Concerto Amsterdam

Jaap Scroeder, violin

Jacques Hoffman, violin

Franz Lachner: Nonett f-MolI für Flöte, Oboe, Klarinette, Horn, Fagott

Andante – Allegro moderato

Menuetto: Allegro moderato

Adagio

Finale: Allegro ma non troppo

Danzi-Quintett

Frans Vester, flute

Marten Karres, oboe

Piet Honingh, clarinet

Brian Pollard, bassoon

with:

Jaap Schroeder, violin

Joke Vermeiden, viola

Anner Bylsma, cello

Anthony Woodrow, double bass

ENGLISH NOTES TO THIS SET

Donaueschingen

Few courts in southern Germany have such a fine musical tradition as the Court of Donaueschingen. This rather sleepy residence of the Princes of Fürstenberg serves as a model for unconventional and unbureaucratic music-making. During the second half of the 18th century and the first half of the 19th century the court orchestra there enjoyed a high standard of achievement, and since 1921 Donaueschingen has been a favourite centre for contemporary music.

Whereas during the Renaissance and Baroque periods the music of this court was only of significance locally, the establishing, around 1762, of a proper court orchestra under the patronage of Prince Joseph Wenzel, himself a good pianist and cellist, saw the advent of a musical era that was to flourish right up to the death of Prince Karl Egon II in 1853. Each week at the palace three concerts of chamber music were given in which artists of international fame often took part. In 1766, for instance, Leopold Mozart and his children performed there. Unfortunately the works for violoncello which Mozart had to write under the watchful eye of the Prince have been lost. The court’s connection with the Mozart family was kept up for a long time. As late as 1786 Mozart sent the Prince a list of his „latest births“, at the same time offering his services as court composer. Up until this time the repertoire of the court orchestra had consisted mainly of works by masters of the Mannheim and Viennese schools, and a few by Bohemian composers. From 1789 onwards the music at the court was in the hands of Karl Joseph von Hampeln, a concert violinist and quartet player from Munich. It was he who managed to procure the services of several distinguished performers and composers. Among them was, for example, the oboist and composer Joseph Fiala, whom Mozart regarded very highly. „An adornment to the orchestra“, Kala was employed at Donaueschingen from 1792 as oboist, cellist and viol player. Mozart had made his acquaintance in Munich in 1777 at a concert of music for wind instruments, and said of him: „One can easily tell they have been trained by Kala. They played some of his pieces, and I must say they are really attractive. He has good ideas.“

Fiala, for his part, admired Mozart’s works tremendously. Leopold Mozart, however, did not always entirely trust his son’s admirer: „Questo uomo non fa confidenza ai suoi amici, come gia sapete, é Boemo.“

Fiala died at Donaueschingen in 1816, highly esteemed and revered. Mozart’s opinion of his works is fully confirmed by his Quartet for Oboe and String Trio presented on this recording.

In 1790 the court orchestra still comprised only 18 players, but with the onset of the Romantic movement and the appointment by Prince Egon II of Konradin Kreutzer as court Kapellmeister it was to reach hitherto unattained heights. Kreutzer took up his post on September 20th, 1818, and remained there until March 1822 as director of the orchestra, which in the meantime had increased to 28 players.

Under Kreutzer’s direction there were weekly concerts of high niveau. He wrote that he was now „swimming in music“, and that, encouraged by the Prince, every member of the orchestra was „inspired by great enthusiasm for and delight in his art“, and that visitors expressed their „amazement at the precision and impressiveness of this small orchestra“. Some of his more important works were written at Donaueschingen, including the Scenes from Faust, his Te Deum, his Septet Opus 62 (which shows a marked indebtedness to Beethoven’s Opus 20) and his Quartet for Clarinet and String Trio.

The compositions recorded here, the first of Kreutzer’s numerous works to be issued, reveal a master, who pledged himself to the German Romantic movement at its very outset, and, who, without any doubt, had great musical personality.

In December of the year 1822 yet another important personage in European musical life took on the post of court Kapellmeister and composer at Donaueschingen. It was the Bohemian violin virtuoso and composer Johannes Wenceslaus Kalliwoda, who already enjoyed an international reputation. A close friend of Carl Maria von Weber, and held in high esteem by many of the German Romantics, he seemed destined for a brilliant career. No less a person than Robert Schumann acclaimed in Kalliwoda’s 5th Symphony „the delicacy and sweetness prevailing in all the movements, its numerous fine and subtle features and its brilliant instrumentation“. His work at Donaueschingen, which continued until 1850, his international reputation as a composer and his instrumental music – regrettably completely unknown today – would justify devoting an entire recording to this „lesser master of the German Romantic movement“. For this reason we shall not go into any more details of his work here. Instead, for our present purposes, we shall turn our attention elsewhere.

An outstanding characteristic of the court at Donaueschingen was its readiness to accept the „modern“ music of the beginning of the 19th century. To illustrate this we are introducing on record for the first time the work of an unjustly forgotten German composer of great merit, Andreas Späth, whose name means something to only few present-day musicologists. As Kapellmeister to the Duke of Gotha and Coburg Späth accompanied him on long journeys all over Europe, taking in Vienna „in order to study the finer points of composition there.“ His works were published by Schott – Mainz, Andre – Offenbach, and Paccini – Paris, and were sold all over Europe. His Nonet Instrumental, which, like all his compositions, has never before been recorded, was composed in 1840 and is dedicated to Karl Egon III of Fürstenberg. The basis for our recording is an autograph from the library at Donaueschingen.

It only remains to be said that it is not the purpose of this box to present the entire musical history of Donaueschingen. We have, instead, selected a number of items of musical value, intending to attract the attention of the musical world to a city and a court that, through the boldness of its ventures both past and present, is a living monument to music.

Thurn und Taxis

The numerous manuscripts which, in the 18th and 19th centuries, were in the possession of Southern German princely families and which are now awaiting ressurrection in libraries and archives are of inestimable musical value. They date from a culturally rich period in which numerous princes maintained their private operas and orchestras and rivalled one another in attracting the best composers and musicians: Danzi, Cannabich, Rosetti Reicha, Fiala and Kalliwoda were in their time highly estimated orchestra leaders, who composed music in order to entertain and to display the dignity of those who reigned by the Grace of God.

In Germany the name „Thurn and Taxis“ is inseparably bound up with the origins of a postal service. The connection goes right back to the end of the 15th century when members of the family began to set up postal links between all the larger towns of the „Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation“. The family, which originally came from Northern Italy, working with great resourcefulness and energy, gradually established a permanent and reliable service. A hereditary title was created, and, in 1615, the family of Thurn and Taxis was officially appointed Postmaster General to the Empire. In 1624 Lamoral von Taxis was given the title of count and in 1695 Eugen Alexander was made a Reichsprinz. The family residence, during the 16th century in Brussels and after 1702 in Frankfurt on Main, was, in 1748, transferred to Regensburg, the seat of the permanent Reichstag (Parliamentary Diet). This move was brought about by Prince Alexander Ferdinand’s additional appointment as Chief Commissioner of the Reich, a post which necessitated his continual presence in Regensburg, where he had to represent the Emperor at the Reichstag. This office was held by the Thurn and Taxis family right up to the dissolution of the Empire in 1806. The duties involved were mainly ceremonial. On the occasion of the Emperor’s accession to the throne it was the Prince to whom the city paid homage. Soon after moving to Regensburg Alexander Ferdinand had assembled his own court orchestra, and by 1755 we find 14 court musicians listed in the „Etat de la musique“. By 1760 the princes had opened their own French theatre. Prince Carl Anselm, who took over the title in 1773, was even fonder of music and the theatre than his father had been. His enthusiasm and generosity enabled the orchestra to expand and the court theatre to be enlarged. The Prince appointed Theodor Freiherr von Schacht, who had been in the service of the family since 1771, as Director of the Court Music and Opera. Under the Prince’s generous patronage von Schacht succeeded in creating a flourishing musical centre. First-rate instrumentalists were acquired for the court orchestra, many of them from foreign countries. Croes from the Netherlands, Kaffka and Pokorny from Bohemia, Touchemolin from France and two Italian virtuoso wind players, Agostinelli and Palestrini were all engaged at Regensburg. Schacht could justifiably boast in a letter of 30.1.1796, „Since anno 1773 I have been in charge as director of the department and flatter myself that I have attained for His Highness’s orchestra a reputation of the first order.“ Schacht spared no effort to provide a continual flow of new works to delight his music-loving Serene Highness, works representative of very contemporary trend. The royal collection in Regensburg today contains music by 378 different composers. The repertoire was also enriched by contributions from a number of Thurn and Taxis musicians. The content of the 3000 manuscripts and prints that make up the Regensburg collection clearly indicates that the wind instruments enjoyed the greatest popularity at the Thurn and Taxis court. As well as numerous flute and oboe concertos there are concertos for clarinet, basset horn, bassoon and horn. It is from these that we have made our selection for this recording.

Theodor von Schacht, the composer of the Clarinet Concerto in B flat, was born in Strasbourg in 1748. After his early musical training in Regensburg, where he studied under Küffner and Riepel, both court musicians, he went to Stuttgart in 1766. There he became a pupil of the Italian composer Jommelli. Two years after returning to Regensburg in 1771 he was appointed Director of Court Music, a post he retained until his retirement in 1805. Between 1774 and 1778 and from 1784 until the closure of the court theatre in 1786 he was also Musical Director for Italian Opera. In the summer of 1805 Schacht journeyed to Vienna in the hope of finding some official recognition of his musical ability there. This successful enterprise was crowned by meetings with the Archduke Rudolf, Beethoven’s friend, and Emperor Napoleon I, the latter commissioning six masses from him. Schacht returned to Germany in 1812. He died in 1823 in Regensburg, where 17 years earlier, in 1806, the court orchestra had been disbanded. There are 155 works by Schacht in the Regensburg collection, including 25 symphonies, 37 concertos, 21 sacred works and 5 operas.

Franz Xaver Pokorny was born in Bohemia in 1728. In 1753 he became a court musician at the court of Count Oettingen-Wallerstein and in 1754 studied composition in Mannheim under Stamitz, Holzbauer and Richter. In 1770 he left Oettingen at his own request and entered the service of Thurn and Taxis in Regensburg, where he worked as violinist and composer up until his death in 1794. The Regensburg collection has 198 works by Pokorny, most of them scored in his own hand. In addition to 109 symphonies there are 66 concertos, divertimenti, serenades and other chamber music compositions.

Karl Friedrich Abel was born in Cöthen in 1723. He was a skilled player of the bass viol and was a member of the Dresden Court Chapel from 1748 to 1758. He went to London in 1759 and settled there, introducing, in partnership with the „English Bach“, Johann Christian, the famous series of concertos known as the Bach-Abel concerts. He died in London in 1787. His compositions show close links with the Mannheim school and, probably for this reason, found particular favour at the Regensburg court. As well as his Concerto for Oboe, Clarinet, Violin and Orchestra, recorded here, there are 12 symphonies included in the Regensburg collection. On the original copies of the solo parts used in our recording we can see the names of the Regensburg soloists written in Schacht’s own hand: the oboist Hanisch, the clarinetist Schierl and the violinist Kaffka – all members of the Thurn and Taxis court orchestra for many years.

Franz Anton Hoffmeister was born at Rottenburg on Neckar in 1754. He turned to music at an early age and eventually became one of Vienna’s best-known music publishers, publishing many of the works of his famous contemporaries (Mozart, Haydn and Beethoven). He died in Vienna in 1812. Hoffmeister was a much respected composer himself, and, included in the numerous publications that Schacht obtained from him were many works of his own. At Regensburg there are copies of the orchestral parts for 8 symphonies, a flute concerto and the clarinet concerto recorded here, as well as printed editions of 21 string quartets.

Oettingen-Wallerstein

The Ries is a flat, fertile basin of volcanic origin lying between the Swabian and Franconian hills. Here, not far from Nördlingen, the Counts of Oettingen-Wallerstein had their residence. The family had lived in the district since the middle of the 16th century and their magnificent residence appears quite early in the annals of musical history. It was during the time of Count Kraft Ernst, however, that music at the Wallerstein Court really began to flourish. Kraft Ernst, soon to be made a Reichsprinz by the Emperor, on succeeding his father in 1773, immediately instituted a court chamber orchestra, engaging several excellent musicians, many of them Bohemian. In less than ten years the Prince had a fine orchestra of 11 violonists, 2 oboists, 2 flautists, 2 horn players, 1 bassoonist, 1 viola player, 1 cellist and 1 double-bass player. The Wallerstein court musicians were acclaimed by the writer Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart, an observant chronicler of the period particularly in respect of its music, who admired their ability to produce „the most subtle and practically imperceptible gradations of tone“. No less an authority than Joseph Haydn himself affirmed that the Wallerstein Court Orchestra performed his symphonies with greater precision than any other orchestra he knew.

The music collection in the Royal Harburg Library records that the Wallerstein court played works by masters of the Vienna and Mannheim Schools. The court made a point of keeping in constant touch with the international world of music, as the visits of both Mozart and Haydn to Wallerstein clearly show. The repertoire, however, included a large number of works by resident musicians as well, the first one of note being Ignaz Franz von Beecke, a friend of Gluck’s and well versed in the current musical trends in Paris and Mannheim.

Franz Anton Rößler was in the service of the Oettingen-Wallerstein court for many years, as a double-bass player and as conductor of the orchestra. Like many of his contemporaries he italianized his name, being known as Antonio Rosetti. Rößler was born in 1750 in Northern Bohemia (near Leitmeritz). Much against his personal inclinations he was forced to enter Holy Orders, but eventually obtained a dispensation in order to devote himself entirely to music. In 1773 we find his name mentioned for the first time listed in the Wallerstein accounts. In 1789 he left the Wallerstein court to take up a more lucrative post at the court of the Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin (in his last few years at Wallerstein he had been getting more and more heavily into debt). Schubart spoke of him as „one of the most popular composers“ of his day. Rößler’s Horn Concerto in F major, recorded here, was written during his time at Wallerstein.

Joseph Reicha (uncle of the composer Antonin Reicha, the teacher friend of Beethoven) was born in 1746 at Klattau (Klatovy), South West Bohemia. He was a violoncellist of considerable distinction. For 11 years, from 1774 to 1785, he was in the service of the Oettingen-Wallerstein court, after which he obtained a post at the court of the Elector of Cologne. In 1789 he was appointed conductor of the new Electoral National Theatre Orchestra in Bonn, the orchestra in which from time to time the young Beethoven played the viola.

Johann Georg Nisle, born at Geislingen (Württemberg) in 1731, was for several years hautboist in the Württemberg Ducal Guard at Ludwigsburg. In 1773 he entered the service of Prince Kraft Ernst at Oettingen-Wallerstein as a horn player and from 1777 until his death in 1788 held posts at the courts of Neuwied, Hildburghausen and Meiningen. Accompanied by his gifted sons, whom he set up as child prodigies, Nisle toured extensively, securing for himself a wide reputation as a horn virtuoso of phenomenal skill.

Shortly after the death of Prince Kraft Ernst the principality of Oettingen-Wallerstein was annexed to the Kingdom of Bavaria.

A year later, in 1807, the court orchestra had to be disbanded (the entire staff „with the exception of liveried servants“ was dismissed). It was not until 1812, when Prince Ludwig Kraft was able to take over the government, that court musical activities could be organised again. A court orchestra was re-formed, and in 1818 the distinguished musician Johann Andreas Amon was acquired as director. Once more music began to flourish at Wallerstein.

Johann Andreas Amon, born in Bamberg in 1763, was a pupil of the famous horn virtuoso Johann Wenzel Stich (alias Giovanni Punto), a friend of Beethoven’s. An accomplished horn player himself, he undertook extensive concert tours, his travels taking him to Paris, where he studied composition with the successful opera composer, Antonio Salieri. He became a personal friend of both Haydn and Mozart. In 1789 he was appointed Municipal Director of Music at Heilbronn and in 1817 he entered the service of Prince Ludwig Kraft at Oettingen-Wallerstein, initially as director of the choir school. Amon composed works of all categories, one composition worth particular mention being a German Mass, which was a setting of words by Prince Ludwig Kraft.

Würzburg

Constructed in the first half of the 18th century and brilliantly decorated by the leading artists of the day, the superb, lavishly built Würzburg Residenz came to symbolize a culturally active court of which music, too, was an integral part. Under the patronage of the Prince-Bishops Friedrich Karl von Schönborn and Adam Friedrich von Seinsheim music here reached its zenith. Up until the middle of the eighteenth century all the important musical figures at the court, the Kapellmeisters and composers, were Italian, but later more and more local talent came to the fore. Without opera, concerts and festive church music court life was unthinkable. The court orchestra provided for both court ceremonial and pleasant diversion. As was customary at the smaller courts some of the musicians also served as valets or footmen or were otherwise employed.

When, in 1802, as a result of the secularization of the ecclesiastical principalities, the Episcopal Palace of Wurzburg fell to Bavaria, music at the court had long been largely confined to church services, and, with the end of the Wurzburg Grand Duchy (1806 – 1814) court music ceased to exist altogether. For several decades the citizens of Wurzburg had been upholding the city’s musical tradition in lieu of the court. Thus after 1770 we find chamber music concerts being organized by various groups of music-lovers in the town and a Collegium musicum. In 1803 the city instituted something which was to set an example for the whole of Germany. The musical journal, Leipziger Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung, reported in June 1804 that: „In Wurzburg there has been in existence for some time now an extremely well supported musical society made up of professional men, at the head of which was the young lawyer Herr Fröhlich, a most able musician in respect of both the theory and practice of the art. His fruitful efforts have procured for him now a position as… teacher and director with a salary of 400 guilders. For those young persons wanting to follow an academic course in music this is an institution indeed quite unique in Germany, and deserves to be copied by other universities.“ Thus Germany’s oldest state music academy came into being.

Franz Joseph Fröhlich (1780- 1856), who was born in Wurzburg, directed the „Royal School of Music“, as it was then called, for no less than 54 years, during which time its reputation grew steadily, both as an institute of learning and as a concert centre. Unfortunately, as the result of wars, practically all of Fröhlich’s compositions have been lost. His Serenade for Wind Instruments and Strings, one of the very few works from his pen remaining to us, is indeed proof of his great ability.

Joseph Küffner (1777 – 1856), son of a Wurzburg court Kapellmeister, was himself a court musician at Wurzburg and also a military director of music. After 1814 he devoted himself entirely to composing. According to one of his contemporaries Küffner believed „that by paying homage to contemporary taste he could reach a wider public and better recommend himself. His first three serenades were written for guitar, flute and alto and were received with rapturous applause.“ These attractive period pieces still have a definite appeal today, not least on account of the delightful way the three instruments are used. Küffner produced several hundred works altogether. He was held in considerable esteem in the mid-nineteenth century, as the following extract from Gaßner’s dictionary of music (1849) shows: „Küffner has proved himself to be an excellent composer and is highly regarded in all countries. He leads a simple life, his little house and garden cut off from the rest of the world, so neat, pretty and clean that one is almost envious, and showing from its exterior that it is the home of a contented man.“

Although Küffner being a fashionable composer was undoubtedly very popular, Friedrich Witt (1770 – 1836) must be regarded as Wurzburg’s greatest musician after the turn of the century. Witt was the last of the Wurzburg court Kapellmeisters and continued to run the city’s music after 1814 as well, directing church, theatre and concert performances. His name recently became known again in our century when it was discovered that he was the real composer of the „Jena“ Symphony, previously thought to be an early work of Beethoven’s. Before moving to Wurzburg he was employed at the court of the Prince of Oettingen-Wallerstein as violoncellist and took lessons there from Antonio Rosetti, who was the court Kapellmeister at the time. At the Wallerstein court solo concertos for one or two horns enjoyed much popularity and consequently Witt was also inspired to write some. His concert in F major for two horns, a work demanding a considerable amount of technical accomplishment, certainly justifies the contemporary allusion to „the brilliant wealth, the forcefulness and diversity of his ideas“. It is not without fascination to recall that the young Richard Wagner worked under Friedrich Witt, when the latter was choral director at the Wurzburg theatre, and composed his first opera „Die Feen“, there.

Nürnberg

Scarcely any other town of comparable size reflects the course of German history, with all its vicissitudes, as does the old „Free Imperial City“ of Nuremberg; and, woven into the intricate web of political, economic, religious and cultural developments, music, in particular, stands out vividly in all its varied forms. In the 14th and 15th centuries it was chiefly the Community’ s flourishing foreign trade that enabled the arts to enjoy similar good fortune and develop to an unprecedented degree. In the first half of the 15th century Nuremberg had already produced within its ancient walls the first great name in the musical history of Germany, Konrad Paumann (c. 1415 -1473), the great pioneer of organ and lute playing. Closely connected with the development of organ music there grew up at the same time another new art-form, the German Lied, whose main sources were also to be found in Nuremberg: the „Lochamer-Liederbuch“ (1452 – 1460) and the song-book of Hartmann Schedel (1460 – 1467).

At the time of Albrecht Dürer (1471 – 1528), when Nuremberg was at the peak of its cultural and political development, the foundations were laid for the two thriving musical industries of the future, instrument making and music printing and publishing. The new humanistic learning of the period also made its presence felt and led to the reform of musical instruction in schools, the driving forces in this direction being Johannes Cochläus and Sebald Heyden. The city produced two composers of note, Conrad Rein, the teacher of Hans Sachs, and Wilhelm Breitengraser. Adolf Blindhamer, former court lutenist to Emperor Maximilian I, and his pupil Hans Gerle and Hans Neusiedler became leading exponents of the art of lute-playing and also produced excellent compositions for this instrument. Although the middle of the 16th century saw a decline in the city’s musical activities, from 1575 onwards the city received renewed impetus from Friedrich Lindner and, in particular, Leonhard Lechner, who secured a place for Nuremberg again among the musical centres of Southern Germany. As a result of the successful blending of the old German and Flemish musical styles with the new Italian madrigalian devices in vocal writing a „new German Lied“ emerged, mainly due to the work of Lechner, which found its culmination in the masterly compositions of Hans Leo Hassler.

It would seem that the most concentrated, substantial picture of Nuremberg’s musical life is presented in the Baroque era, when the city directed its cultural efforts along a course completely independent of any neighbouring musical activities. This is all the more remarkable as the political and economic importance of the city had noticeably declined during the Thirty Years’ War and after the devastating plague years of the 17th century. In contrast to the prevailing pattern of musical life as witnessed in the other „free imperial cities“ and royal courts of Germany at that time, the focal point of which was always the reigning chief conductor or choirmaster, Nuremberg’s musical activities revolved round its organists. The work of these Nuremberg masters was strongly determined by the great tradition of organ playing which had grown up in Nuremberg and continued to be handed down from teacher to pupil for a period of over five generations, stretching from Johann Staden through to Pachelbels son Wilhelm Hieronymus and the threshold of the classic era. Such continuity of teaching was quite unique in Germany and one can with justification speak of a „Nuremberg School“: Staden was the teacher of Johann Erasmus Kindermann, whose pupils Heinrich Schwemmer and Georg Kaspar taught Johann Krieger and Johann Pachelbel. A flowing cantabile style of writing, tight-knit formal construction, a simple tunefulness and lack of any overdramatic pathos characterized the Franconian-Baroque, Nuremberg style.

Johann Matthäus Leffloth was able to benefit from the musical heritage of the „Nuremberg School“. Born in February 1705, the son of a Nuremberg merchant and organist, he received his early musical instruction from Wilhelm Hieronymus Pachelbel and, aged only 18 years, was appointed organist of St. Leonhard’s. The promising young genius, however, died in October 1731 at the early age of 27. His compositions for keyboard instruments clearly show the influence of the Italian style. The fact that his Sonata for Viola da gamba and Harpsichord in C major, recorded here, was once erroneously thought to be by George Frideric Handel is proof enough in itself of the substance of this composer’s works.

Although in the 18th century Nuremberg, compared with other South German musical centres such as Mannheim, Munich and Vienna, was somewhat out of the mainstream of contemporary musical activity, it, nevertheless, in that period too, played a significant role. Evidence of this is provided by the music printing and publishing trade, which was thriving once again. It was to the Nuremberg music engravers and publishers Christoph Weigel and Balthasar Schmid that Johann Sebastian Bach himself entrusted the printing of three of his works (few of which were ever printed during the composer’s lifetime). It is true that some of the city’s talents had to seek their fortunes elsewhere. Thus Johann Christoph Vogel, born in 1756 into an old Nuremberg family of lute and violin makers, decided to settle in Paris in 1777, where, like Leffloth, he suffered an untimely death at the age of 32. Vogel always regarded Christoph Willibald Gluck as his real teacher in composition. He himself was considered one of the most important operatic composers between Gluck and Mozart. Whereas a revival of Vogel’s operas in our days has proved unsuccessful, there is a growing interest in his instrumental works, a number of which are becoming increasingly popular. Written originally to provide for the court orchestras of the French nobility, they have a charming musical freshness which appeals today. One instrument that features prominently in much of Vogel’s chamber music is the clarinet. This is significant as it was from the city of Nuremberg that this instrument set out on its triumphal progress through musical Europe, for around the year 1700 Johann Christoph Denner of Nuremberg produced the first key-chalumeau, the immediate forerunner of the clarinet.

The composer Johann Georg Heinrich Backofen was also a virtuoso clarinetist. The Backofen family, of which there were numerous branches, was the one musical family to achieve any prominence during Nuremberg’s last years of glory as a „free imperial city“. J.G.H. Backofen was born at Durlach in 1768. In 1780 he and two of his brothers became apprenticed to Capellmeister Georg Wilhelm Gruber in Nuremberg. He remained in Nuremberg until 1806 and died in 1830 in Darmstadt, where he had been a member of the Court Orchestra. In addition to composing, Backofen also compiled excellent text books on the principles of playing both the clarinet and the harp. His concertos and concertante symphonies for various solo instruments and orchestra, which were widely performed during his lifetime, date, for the most part, from his years in Nuremberg, a time when the former medieval Franconian metropolis, through people like Wilhelm Heinrich Wackenroder and Ludwig Tieck in particular, was already being „discovered“ by the new Romantic movement.

Augsburg

Augsburg’s golden age in the field of music was the 16th Century. It was then that the Free Imperial City of Augsburg, the leading metropolis of trade at the time, was able to develop into one of the most important centres of music in Europe, a fact which was due to no small degree to the patronage of the Fugger family. The Thirty Years War, as well as political changes, seriously affected the city’s cultural life, however soon after 1648 the interest in music was revived anew. The Church was now joined by the middle classes in its efforts to foster music. „This is not the place where great singers or virtuosos can be well paid. Rather, it is more important that there are musicians who love their art and try to perfect their skills so as to satisfy their own keenness. As there is no shortage of such persons, various musicians can gain honour in concert performances.“ This was written in a contemporary city chronicle.

In 1712 Philipp David Kräuter, the cantor and also one of Johann Sebastian Bach’s pupils founded a civil „collegium musicum“, which attracted many of Augsburg’s lovers of music and professional musicians. Leopold Mozart (1719-1787), the son of an Augsburg bookbinder, is bound to have received considerable stimulation from the activities of this group during his years at grammar school (up until 1737). Even after shifting to Salzburg, he still kept in close contact with the group, which was reorganized in 1752 and from then on was called the „Music-making Society at the Baker’s Hall“ („Musikübende Gesellschaft zum Beckenhaus“). Once a week music was played in the guildhall of the Augsburg bakers. Music was also played before a large audience at the inn „Zu den drei Königinnen“. In charge of this „eminent and praiseworthy collegium musician „ (Leopold Mozart’s words) was Anton Christoph Gignoux who, according to Mozart, „could not be spoken of highly enough“. Gignoux, an Augsburg manufacturer of calico and an amateur painter, was on friendly terms with the Mozart family. The orchestral works of Leopold Mozart enjoyed a high degree of popularity at this „Music-making Society“. In 1756, the year in which Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was born, the divertimento „Die Bauernhochzeit“ („Peasant Wedding“) and „Die musikalische Schlittenfahrt“ („Musical Sleighride“) were accorded abundant applause when first performed at society concerts. As a result the Salzburger „by choice“, who was held in very high opinion in his native town, was asked to send more of his „musique“ to Augsburg. We can therefore assume that works such as the Concert for two Horns (1752), the Sinfonia di Camera with a solo violin and a solo horn (1755), the Sinfonia da caccia or Hunting Symphony (1756) and the Sinfonia burlesca (1760), remarkable for the absence of violins in the orchestra, were also heard here. The works referred to last were closely related to the popular symphonies „Peasant Wedding“ and „Musical Sleighride“. A certain instruction should be followed when playing the Hunting Symphony, the first movement of which is distinctly reminiscent of the Volkslied („folk song“) „Frisch auf zum fröhlichen Jagen“. According to the instructions given, it is necessary to have „several dogs which bark, the others must cry together ho ho etc., however only for 6 bars“. The Sinfonia burlesca indicates close relationship with the Comedia dell’ arte by virtue of the headings for movements 3 (II Signor Pantalone) and 4 (Harlequino). It may have been the music accompanying a pantomime.

Among the composers in Augsburg Friedrich Hartmann Graf (1727-1795), the musical director of the Lutheran churches, was one who, above all, was regarded very highly. He came from Thuringia, had been in charge (for a time) – with Georg Philipp Telemann – of public concerts in Hamburg and, after lengthy and successful travels throughout Europe as a virtuoso flutist, was called to the Free Imperial City of Augsburg. In 1779 Paul von Stetten said the following about Graf s works for the flute: „The compositions for his favourite instrument are highly regarded by flute experts and are exceptionally popular, especially in England, Holland and Switzerland, as well as at German courts“. Graf – whom W. A. Mozart had judged too critically after their meeting in Augsburg in 1777 – set up a general „city concert enterprise“ in 1779. He later succeeded Johann Christian Bach as head of the Professional Concerts in London, was awarded a doctor of music from Oxford University and became an honorary member of the Musical Academy in Copenhagen,

Franz Bühler (1760-1823), a generation younger than Graf, became Cathedral Kapellmeister („musical director“) in 1801 and thus occupied the most important position in Augsburg as far as catholic chapel music is concerned. As P. Gregor he had been a Benedicter for 10 years at the monastery „Hl. Kreuz“ in Donauwörth. Released from the Benedictine Order in 1794, he had then become an organist in Bozen. His numerous musical works for the Church, which were written with a light hand, were well-known for a long time throughout Southern Germany and beyond. Bühler’s instrumental compositons were less well-known however; the Grand Sonate for piano, clarinet 2 horns and string instruments, which was published in 1804, is the most noteworthy of all these compositions.

München

What, at the time, was played at banquets, for recreation, for family reunions, visits and burial ceremonies has now been revived. Our series presents a recording of these musical treasures (symphonies, concerts, chamber music, sonatas etc.). The collector will hail it as an enrichment of his repertoire with the same gratefulness as those who are interested in the history of Southern Germany. The series offers a splendid opportunity to get acquainted with the musical heritage of a region rich in tradition.

A comprehensive description of the musical life in Munich in the 1770’s has been left to us by an unknown contemporary observer who wrote: „(…could be found): A well organised orchestra under its maestro Bernasconi, who, as his numerous compositions showed, devoted much of his time and energy to it; an Italian opera which ran during Carnival time, usually with a work composed by some accomplished foreign master and performed by famous singers, including in their time such brilliant castratos as Farinelli and Guadagni, to which were admitted, free of charge, the numerous music-lovers and members of the educated classes who eagerly poured in from the neighbouring seminaries, monasteries and country towns to glean new ideas for their own musical efforts of the coming year; frequent court concerts of amateur music-making; and, almost without exception, a daily chamber music concert, an entertainment which the Elector, himself a skillful performer on the viola da pompa and an esteemed amateur composer, much liked to attend of an evening. In addition, there were musical performances of various kinds in all the larger churches of the city – the Jesuits enjoying the full splendour of the majestic sounds of trumpets and drums, the Augustinians favouring a more modest, gentle mode of expression: during Lent meditations and oratorios, including Metastasio’s passions, from the pens of the solemn Jommelli and the well-pleasing Mysliweczek.“

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart appears to have been greatly charmed by the city of Munich („I love being here“ he is known to have exclaimed). Just how attractive his stay there in 1784 must have been, we can read from his own travel notes: „This city is one of the most beautiful in all Germany, as everyone here will agree. One can live here very cheaply, very comfortably and very freely. Paradisial gardens, palaces worthy of the gods, incomparable concert performances and theatrical productions as magical as fairyland.“ After the oppressive narrow atmosphere of the life in Salzburg, Munich’s more generous living and abundance of stimulating new ideas and opportunities must have shown up in especially glowing colours to Mozart. It was in the sixties that Mozart had actually first visited Munich. The child prodigy and his sister, Nannerl, had been taken on tour by their father, Leopold Mozart, and invited to play for the Elector at his Residenz and at the Nymphenburg Palace, and for Duke Clemens at his Garden Schloss just outside the city. Later, in 1774, he was commissioned to write an opera for Munich – „La Finta giardiniera“. Even after the first rehearsal Father Leopold was able to write home proudly to Salzburg, „The whole orchestra and everyone that attended the rehearsal say that they have never heard any music more beautiful, an opera where each aria is as lovely as next. Whereever we go people are talking about it.“ The premiere was on January 13th, 1775, at the Salvator Theatre. Mozart wrote to his mother, „God be praised! Yesterday, on the thirteenth, my opera was launched, and was such a success with the audience, Mama, that I just could not begin to describe you the noise! In the first place the theatre was packed so full that lots of people had to be turned away. And after each aria there was such a terrible din with all the clapping and yells of „viva maestro“.“

Right up to the end of Carnival time the Mozarts were busy attending all the masquerades, making the most of their opportunity. On February 15th Leopold Mozart wrote; „We have decided not to go to a masquerade today, we must rest. It will be the first one we have missed. „ During the remaining time Mozart occupied himself with composing. Probably stemming from this period are a mass, a Kyrie fragment, an offertory, a piano sonata, a sonata for bassoon and violoncello and the two Wind Divertimenti KV 196 e and f. These two last-named pieces are gay, light-hearted works, each consisting of five movements, typical of the sort of music that would be played by the court or town musicians during dinners or at small social gatherings to entertain the guests. Mozart himself was treated to a similar musical diversion about two years later when he was lodging with the music-loving innkeeper Herr Albert, who kept a winecellar in the Kaufingergasse in Munich. Mozart reported: „At about half past nine a little band of five musicians arrived, 2 clarinets, 2 horns and 1 bassoon. Herr Albert, whose name-day it is tomorrow, had let them play in his honour and in mine, and they did not play too badly either. They were the same people that play for the dancing at Albert’s.“

A quarter of a century later, around 1800, Munich was a city with a population of

45 000. In the Residenz Theatre, built by Francois Cuvilliés, about 40 performances of operas were being given a year. In addition to the works of Italian, French and Viennese masters a fair number of operas by local composers were now being included in the repertoire.

A contemporary printed guide to the city lists the following musical entertainments: „At court, from time to time, amateur concerts are organised in the Hercules Room at the Residenz, particularly on gala-days; more frequently, chamber music concerts with vocal and instrumental music are given. The former entertainment may be attended not only by the courtiers themselves but also by the entire court household and, behind a small barrier, more humble members of the public. The latter concerts, of chamber music, are given only by a small selected group of performers. In the ballroom, every year, there are also 12 amateur concerts given with admission through an advance payment of 11 guilders. The profit thus made, after all costs have been deducted, is allotted to the theatre funds.“

In 1778 the court orchestra gained considerable reinforcement through the arrival of the Mannheim Orchestra with Elector Karl Theodor. It now could boast a number of accomplished musicians and composers, whose compositions now made up the main part of its concert programmes. Above all, the works of the Kapellmeister Winter and Danzi enjoyed great popularity. Franz Danzi, who had known Mozart personally, started off as a violoncellist in the court orchestra, and after being granted many leaves of absence over the years for opera and concert performances in Saxony, Bohemia and Italy, where he toured with his wife Margarethe (a pupil of Leopold Mozart), he finally, in 1798, was appointed its Vice Kapellmeister. He later became a close friend of Carl Maria von Weber and is, with justification, considered an important forerunner of the German musical Romantic Movement.

Danzi’s influence on Weber, who was 23 years his junior, may be easily traced, for example, in the Concerto in F major for Bassoon and Orchestra with its concluding Polacca, which clearly points towards the style of similar final movements in Weber’s solo concertos. In this work, as in the Double Concerto in D major for Clarinet and Bassoon, the melodic wealth and harmonic colourfulness characteristic of Danzi’s music are set off to particularly charming advantage. Internal disputes with his colleague Peter von Winter caused Danzi to leave Munich in 1807 and take up another position, as court Kapellmeister in Stuttgart. His compositions, however, long remained favourites on the numerous concert programmes and in the repertoires of the Munich church choirs.

One of the most brilliant periods in Munich’s musical history was the 16th century. The Bavarian Ducal Court Chapel enjoyed at this time a position unequalled in Europe except by the Papal Court Chapel itself. By acquiring the highly-esteemed blind organist Conrad Paumann (c. 1420 – 1473), of Nuremberg, Duke Albert III made Munich for the first time a city of musical importance. Paumann’s tombstone still today has a special place of honour below the organ gallery in the Frauenkirche. One generation later the „greatest German song-writer“ of the century, Ludwig Senfl (c 1486 – 1543), of Switzerland, chose to settle in Munich. Senfl was a pupil of the famous Flemish composer Heinrich Isaac and, as such, found a post allotted to him quite early on in his career at the Imperial Court Chapel, which, at the turn of the century, represented Europe’s most distinguished musical institution. When the music-loving Emperor Maximilian I died, in 1519, Senfl decided to go to Munich, where he was eventually made Court Kapellmeister of the Ducal Chapel. Under his influence the Bavarian Ducal Chapel developed rapidly, modelling itself on the Imperial Court Chapel. As Court Kapellmeister Senfl was required to provide music for an extremely wide variety of occasions: masses, motets, magnificats and hymns for the church services and prayers as well as secular songs and instrumental pieces as suitable entertainment at table and for court festivities. Senfl became the greatest and most prolific writer of German Lieder of the period. No matter what the material to hand, his inexhaustible imagination would spark off ever new flights of creativity.

Ludwig Daser (c. 1525 – 15S9) was born in Munich and became one of Senfl’s successors to the much coveted post of Court Kapellmeister. He held the position from 1552 to 1563. Daser preferred to follow in the musical tradition of his predecessors in his compositions, as his 8-part motet „Benedictus Dominus“, written on 4 consonant cantus firmi, clearly shows.

The year 1556 was to witness a decisive step in the history of Munich’s Court Chapel. Duke Albert V, an ardent patron of the arts, summoned to his service the young Orlando di Lasso (1532-1594), of Mons in Hennegau, already a well-known and highly regarded musician. Munich became the focal point of musical Europe, for Lasso, known by his contemporaries as the „Belgian Orpheus“, became the most celebrated composer of his day, comparable only to Palestrina in Rome. Lasso remained in the service of the Bavarian Court Chapel for nearly 40 years. A true cosmopolitan, travelling widely throughout Europe, he became a composer of universal stature, in whose style all the elements of contemporary European music were united. He represented the „culmination of the Flemish school“, which, since Johannes Ciconia (+ 1411), had for nearly 200 years led Europe in the field of music. His numerous secular songs comprise German Lieder, French chansons, Italian madrigals and Latin humorous songs and drinking-songs. To each genre he brought a supreme mastery practically unmatched in his day. The „Magnificat sexti Toni“ and the hymn „Kombt her zu mir, spricht gottes son“ are fine examples of the type of sacred music he customarily provided for the daily requirements of the chapel, likewise the two 6-part motets „Timor Domini“ and „Timor et tremor“ and the sections of the great doublechorus „Missa vinum bonum“ show the master at his most powerful.

The young successor to the throne, William V, later known as William the Good, became very attached to Lasso, and a warm friendship grew between the two men which was to prove of great value to them both later, in good times and in bad. After his wedding the twenty-year-old William lived at Trausnitz above Landshut, where he maintained a splendid court. With friendly advice from Lasso he built up his own court chapel, which included among its members several noteworthy composers.

Lasso’s fame spread throughout Europe. A deep-thinking man, highly educated and skilled in many languages, he became in addition a much sought-after teacher. The best talent of the land was sent to him for tuition, even Venice sent their subsequently famous Giovanni Gabrieli to Munich for further studies. The singers and musicians of the Court Chapel were frequently notable composers as well, and compete masters of their art in all its aspects. The manuscript copies they produced were for many years thought to be printed, so perfectly were they written.

Lasso was consequently fully occupied as Kapellmeister and Court Composer and at the same time teacher of the choristers, of the instrumentalists and of the best students of composition. To assist him in carrying out his many duties he had a Second Court Kapellmeister, Johannes de Fossa (c. 1540-1603), a Dutchman, of whom a work is included on this record: the Kyrie and Gloria from his Missa „Ich segge ä dieu“, a mass written on a well-known Dutch song. Perhaps the most eminent member of the Chapel around 1570 was the Dutchman Ivo de Vento (c. 1543/45-1575), Kapellmeister of the Landshut Court Chapel and organist of the Munich Chapel. He is the great German song-writer of the late 16th century. His 3, 4 and 5-part songs and his short 5-part motet „Herr dein Wort“ display his undoubtedly great skill. The Austrian composer Leonhard Lechner (1553-1606) also began as a chorister in Munich under Lasso and later under Ivo de Vento at Landshut. His two great masters had a lasting influence on him, inspiring him to develop into Germany’s greatest composer of the turn of the century. His reputation as the „mighty composer“, however, was won during the course of a somewhat hectic career, in which he moved from Munich to Landshut, Nuremberg, Hechingen, and finally to Stuttgart, where he died in 1606.

Jacob Reiner (before 1560-1606),’ regens chori’ of the neighbouring abbey at Weingarten, came to Lasso for tuition and became one of his favourite pupils. The 6-part motet „Mane nobiscum domine“ and the parting-hymn „Behüt euch Gott“ show Reiner to be a composer of considerable merit. The compositions of Anton Gosswin (c. 1546- 1594), Dutch counter-tenor at the Munich Court Chapel and later in the service of Duke Ernst, Prince-Bishop of Freising, and Balduin Hoyoul (1547/8 -1594) give evidence of yet two more leading musicians at the Munich Court Chapel. An institution such as the Munich Court Chapel, unique as it would seem to have been in Europe, required a strong leading personality to keep the many talented individuals together, to care for both their artistic and their human needs. This personality it fortunately possessed: Orlando di Lasso.

Peter von Winter was born in Mannheim on August 28th, 1754. The son of a brigadier, he was taken into the service of Elector Karl Theodor at the early age of ten to play in the Mannheim court orchestra, and so was fortunate enough to experience in its prime the „Mannheim school“, by then famous throughout Europe. The writer Schubart sang the praises of the Mannheim orchestra: „Its forte is like thunder, its crescendo a cataract, its diminuendo a crystal stream rippling away into the distance, its piano a breath of spring. The wind instruments are all employed the way they should be employed: they elevate and carry or enrich and animate the musical flow of the violins.“ Here Winter received a sound musical training, and by the age of fifteen had learned to play the double-bass, later taking up the violin as his main instrument.

When in 1778 the Elector succeeded to the Bavarian throne, most of the Mannheim orchestra, including Winter, moved to Munich the new capital. At Mannheim under the guidance of Abbe Georg Joseph Vogler Winter had already shown himself to be a capable composer. Now in Munich he began to distinguish himself in this field, his ballet music and concertos being most favourably received. The year 1782 saw the first of his numerous operas and Singspiele: „Helena und Paris“. The most successful of these however was „Das unterbrochene Opferfest“, written in 1796. This highly effective „heroic opera“ had its premiere in Vienna and made Winter internationally famous overnight. It was followed by his heroic-comic opera, „Das Labyrinth oder der Kampf mit den Elementen“ („The Labyrinth or The Fight against the Elements“), a sequel to Mozart’s „Magic Flute“ and partly based on it. In 1787 Winter had been appointed deputy-leader of the Munich Court Orchestra and in 1798 he was made principal choral conductor. Up to 1805 he travelled extensively, visiting Naples, Venice, Berlin, Prague, Warsaw, Petersburg, Moscow, Stockholm and London. Although during this period most of his compositions were in the field of opera, he by no means neglected instrumental music, which was equally dear to his heart. On February 29th, 1804, he conducted the first performance of his Sinfonia Concertante for six solo instruments and orchestra at the Redoutensaal in Munich. From then until 1816 his name frequently appears in the programmes of the winter series of subscription concerts given by the court orchestra. Known after 1811 as the „Musical Academy“, this was an institution that formed an integral part of musical life in Munich and still enjoys a high reputation today. Chamber music compositions too, such as his Septet, published in Paris in 1803, were often performed. Winter’s greatest triumph on the concert platform, however, was his Battle Symphony for five orchestras and choirs, performed on April 18th, 1814, at the Cuvillié Theatre in Munich.

On March 23rd, 1814, the court celebrated Winter’s 50 years of service there with a grand anniversary concert consisting of a selection of works he had composed in Munich over four decades. He was awarded the Order of Merit by King Max Joseph of Bavaria, an honour carrying with it a title – he was now known as Ritter Peter von Winter. In the years that followed he devoted himself mainly to the composition of church music and enjoyed high esteem as a teacher of voice and composition. Many distinguished Munich composers owed their training to him.

Not all the works in his wide range of compositions are of the same high standard, but many bear witness to his remarkable ingenuity, and his command of both form and media. Some traits in his music seem to anticipate the Romantic Movement, but on the whole the Classical element prevails. What a contemporary said of his operas may also be applied to the rest of his work: „He possesses neither that fire, that brilliant turbulence that flares up in Jomelli from time to time, enthralling the listener within the space of a few bars, nor the temperament of a Paisiello. Rather he appears adept and ordered, clothed more with the classical elegance of a French tragedian than with the trappings of a British tragic actor. His music has always had ready appeal and provided us with pleasent diversion.

We can gain some idea of what Winter was like as a person from the letters of Carl Maria von Weber and the memoirs of Ludwig Emil Grimm, the painter, and Ludwig Spohr, the composer all of whom often come into close contact with the all powerful Kapellmeister. Spohr writes of a visit to Munich in 1807: „I was often with Winter, taking a delight in his rather eccentric person, which was remarkably paradoxical. Winter, a man of huge stature, with the strength of a colossus, was nevertheless as timid as a rabbit. Blustering with rage on the slightest provocation, he could, however, be led like a child.“ Bettina von Arnim, a friend of Goethe’s and Beethoven’s, soon discovered this, and when, from 1808 to 1809, before her marriage, she was taking voice lessons from Winter, she played all kinds of practical jokes on her teacher.

Peter von Winter died four days after King Max Joseph, on October 17th, 1825. With his death there came to an end a fruitful epoch in the history of music at Munich, an epoch about which there is still much to be discovered. The new king, Ludwig I, was to show less interest in music and more in furthering the plastic and graphic arts.

In March 1800 when the twenty-nine-year-old Karl Cannabich took over the music at the Munich court he had a band of eighty-two musicians and thirty-nine singers in his charge. Born in Mannheim, the son of Christian Cannabich, a highly respected composer and orchestral conductor, he moved to Munich, where he became a violinist in the court orchestra, later going to Frankfurt, where, from 1796 to 1799, he was a conductor at the theatre. The short but successful period during which he was music director in Munich brought to a conclusion one of the most prolific and colourful eras in the musical life of this city, namely its 150 years as an Electoral city. On May 1st, 1806, two months after Bavaria had proclaimed a kingdom, Karl Cannabich died at the age of thirty-five. An obituary notice describes him as an excellent violinist and pianist. His own music has nevertheless long since been forgotten. The charming Concertante for two Solo Violins and Orchestra composed around 1800, however, can still delight music-lovers and is a far better testimonial to the composer’s ability than the writings of any music chronicler.

We can follow the progress of the court orchestra’s public concerts in the years following Cannabich’s death from a report in the „Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung“ dated 1832: „For nearly half a century, in fact since the appearance under the patronage of Elector Karl Theodor of the Mannheim Orchestra, famous now in musical history, concerts have been given every winter by what has been known since 1811 as the „Musical Academy“. At first there were 72 such concerts in which amateurs, travelling musicians, and young artists of all kinds were given the opportunity of becoming known. Later the number was reduced to 6, then to 3. This last winter they stopped altogether. Not even on the Sunday before Easter, a day when from time immemorial there had been an oratorio or psalm, the „Messiah“, „The Creation“, „The Seasons“, was there a performace …. Where are we to seek the causes of this remarkable lack of public interest here? „ One of the main reasons for the apathy of the concert-going public was the fact that Munich had no musical personality to fill the position of Musical Director in the city. A few years later however the situation was to be completely reversed when Munich gained the services of Franz Lachner, born 1803 at Rain-on-Lech. The new Kapellmeister had belonged to Franz Schubert’s close circle of friends in Vienna and brought with him from that city, and from Mannheim, the necessary experience of the concert hall and the theatre. He was a brillant conductor, capable of injecting new life into an orchestra. Under him the Munich orchestra reached a leading position in Germany. Both the high standard of his concert programmes, based upon composers of the Viennese Classical school but taking generous account of contemporary works, and his well-thought out opera repertoire had a decisive effect on public taste in music. Two great musical events saw the culmination of his work – the Munich Festivals of 1855 and 1865. In the field of composition Franz Lachner is known mainly for his opera „Catarina Cornaro“ and his seven orchestral suites. In addition there is much in his wealth of compositions deserving of revival. Of particular musical and melodic charm is his Nonet for Strings and Wind Instruments in F major composed in 1857 and preserved in manuscript, it is a companion piece to the more frequently perfomed nonet by Ludwig Spohr, who was twenty years his senior. Formally, as, for example, in the sequence of the four movements, he strictly adheres to the classical tradition.

Another 19th century Munich nonet we owe to the pen of Joseph Rheinberger, who was born in Liechtenstein but made his home in Munich. Lachner aside, he was probably the most outstanding resident composer at the time. At the early age of twelve he began his studies at the Munich Konservatorium, where he soon attained „a degree of skill and confidence in counterpoint amazing for his age“. Franz Lachner wrote in the fifteen-year-old student’s report: „Thoroughly trained in theory and practice, he performs superbly on the pianoforte and organ, but it is his composition which gives rise to the greatest expectations „. At the age of twenty he was made a professor at the Konservatorium. Later he worked for a short time in the theatre and for many years was a conductor of vocal music.

Regarded highly in the musical world both as a person and as an artist, he enjoyed the esteem of many of his fellow composers and the friendship of Johannes Brahms. The latter observed that he thought Rheinberger had much in common with Franz Schubert. As his biographer Theodor Kroyer points out, his affinity with Schubert lies in his full-blooded music-making, in his revelling in music. Just to what extent Joseph Rheinberger’s own ideas on the nature and purpose of music as an art coincide with those of Schubert is confirmed by these words written by him shortly before his death, „There is no justification for music without melodiousness and beauty of sound. I am well aware that there are many opponents to my point of view, but white is white, not grey or black. Music ought never to sound brooding, for basically it is the outpouring of joy and even in pain knows no pessimism.“ Written 1884 when the composer was forty-five, his nonet, corresponding to Lachner’s in sequence of movements, is a testimony in sound to Rheinberger’s conservatism in music. It is one of the most appealing instrumental compositions in a plentiful collection in which there are still discoveries to be made.

Fast Shipping and Professional Packing

Due to our longstanding partnership with UPS FedEx DHL and other leading international carriers, we are able to provide a range of shipping options. Our warehouse staff are highly trained to pack your goods exactly according to the specifications that we supply. Your goods will undergo a thorough examination and will be safely packaged prior to being sent out. Everyday we deliver hundreds of packages to our customers from all over the world. This is an indication of our dedication to being the largest online retailer worldwide. Warehouses and distribution centers can be located in Europe as well as the USA.

Orders with more than 1 item are assigned processing periods for each item.

Before shipment, all ordered products will be thoroughly inspected. Today, most orders will be shipped within 48 hours. The estimated delivery time is between 3-7 days.

Returns

The stock is constantly changing. It's not entirely managed by us since we are involved with multiple parties such as the factory and our storage. The actual stock can fluctuate at any time. Please understand it may happen that your order will be out of stock when the order is placed.

Our policy is valid for 30 days. If you haven't received your product within 30 days, we're not able to issue either a return or exchange.

You are able to return a product if it is unused and in the same condition when you received it. It must also still remain in the original packaging.