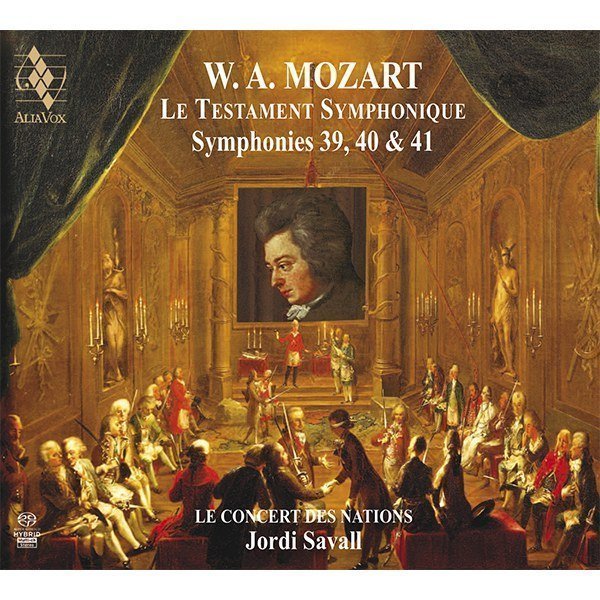

MOZART: Symphonies 39, 40 & 41 – Savall, Le Concert des Nations (2 Hybrid SACD) ALIA VOX

$ 21,99 $ 13,19

By the middle of 1788, at the age of 32, Mozart had reached the height of his creative maturity, dominated by the last three symphonies, absolute masterpieces that he composed in a very short period of time – barely one and a half months. This extraordinary “symphonic massif” consisting of three peaks – Symphony No. 39 in E-flat major, completed on 26th June, Symphony No 40 in G minor, completed on 25th July and Symphony No. 41 in C major, the “Jupiter”, dated 10th August – is unquestionably the composer’s “Symphonic Testament”.

Mozart’s Symphonic Testament

1787-1788

Years of creative maturity, years of distress

By the middle of 1788, at the age of 32, Mozart had reached the height of his creative maturity, dominated by the last three symphonies, absolute masterpieces that he composed in a very short period of time – barely one and a half months. This extraordinary “symphonic massif” consisting of three peaks – Symphony No. 39 in E-flat major, completed on 26th June, Symphony No 40 in G minor, completed on 25th July and Symphony No. 41 in C major, the “Jupiter”, dated 10th August – is unquestionably the composer’s “Symphonic Testament”. A titanic task that he carried out without any specific commission, and, moreover, in extremely precarious personal circumstances, as can be seen from the following letter, penned almost at the same time as the Symphony in G minor (K.550), which was finished on 25th July, which he sent to Michael Puchberg, a member of the Zur Wahrheit (“To Truth”) Masonic lodge, who at that time frequently responded positively to his desperate pleas for help by regularly lending him money:

“My very dear friend and brother in the Order,

Owing to great difficulties and complications, my affairs have become so beleaguered that I find myself having to raise some money on these two pawn-broker’s tickets. In the name of our friendship, I beg you to do me this kindness, but it must be immediately. Forgive me for bothering you, but you know what my circumstances are.”

It is difficult today to imagine a more brutal contrast between the unremitting distress experienced by Mozart in his daily life, particularly in the final years, and the grandeur and dazzling richness of his unique and remarkable musical inspiration. It is therefore a great honour for us to present this “Symphonic Testament” of Mozart, with the recording of his last three symphonies, performed by the orchestra of Le Concert des Nations on period instruments, fully aware of Mozart’s suffering and extreme hardships at a time and in a society that failed to grasp his true musical greatness and to provide him with the moral and financial support he needed to fully develop his incomparable genius.

It was during the process of studying and understanding Mozart’s context and creative motivations at the time of composing his last three symphonies that I realised that it was essential to delve once more into his work and the most significant events of his life during the second half of 1787 and the following years. The summer of 1788 was a period of extraordinary creativity and maturity for the composer, but it was also the moment at which his life crossed the threshold of financial difficulties and declined into the most abject poverty, a situation which constantly obliged him to enter into unsustainable debts by regularly seeking loans from his friends at the Masonic lodges of which he had been a member after being admitted to the Order on 14th December, 1784.

The impressive research carried out by H. C. Robbins Landon during the 1980s clearly confirms Mozart’s links with Freemasonry during the last years of his life, in particular the Masonic lodge Zur gekrönten Hoffnung (Crowned Hope) in Vienna. It is for this reason that we have specially chosen the anonymous painting depicting a meeting of the Crowned Hope Masonic lodge in 1790 as the cover illustration of our edition. Mozart is distinctly visible as the first figure on the right of the painting. To reinforce the visual presence of Mozart in the cover image, we have taken the liberty of replacing the illustration on the wall in the background of the painting with the unfinished portrait of the composer by his brother-in-law Joseph Lange (1789 and 1790). The allegorical painting hanging on the wall in the original (reproduced in the booklet) represents an expanse of water and a rainbow. Given that the rainbow which appeared after the Flood, is a symbol of hope in the Bible and in Masonic iconography, it must have been obvious to the initiated that the painting depicted the Crowned Hope Lodge.

These links with Freemasonry are further corroborated by the recent discovery of an authentic document in which Mozart is referred to as member

Nº 56: “Mozart Wolfgang: Kapell Meister III Degree”.

We also know that Mozart’s most important Masonic work, the Maurerische Trauermusik (K.477), was performed in 1785 at the funeral following the death of two members of that lodge – Georg August, Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (who died on 6th November) and Franz, Count Esterházy von Galántha (who died on 7th November). As the count was a brother of the lodge, a funeral was held there on 17th November with the participation of an orchestral ensemble as extraordinary as it was fortuitous, including the two brothers Anton David and Vincenz Springer, who played the basset horn parts, very likely joined by Mozart’s friend Anton Stadler on the clarinet. We entirely agree with Robbins Landon when he writes: “The dense symbolism of this Masonic Funeral Music shows that Mozart was thoroughly imbued with the theories and philosophy of death and their relevance to the first degree of the Order.”[1]

Two years later, in 1787, Mozart began the year under more auspicious circumstances following the enthusiastic welcome he had been given in Prague, a city which offered him everything that Vienna had denied him: success, official support, a stage and a theatre company. But he was at a critical juncture and he turned the offer down, saying: “I belong too much to others, and too little to myself.” He needed solitude in order to compose and think. Over the following months, various factors closely linked to his personal life were to have a profound effect on him: the departure from Vienna of Nancy Storace (who had sung Suzanne in The Marriage of Figaro), thus drawing to a close the sweetest love of his life, the death of his third child, as well as that of his friend Hatzfeld, and the news (received on 4th April) of his father’s worsening state of health and his eventual death, which occurred in Wolfgang’s absence on 28th May, 1787.

It was at this time that he fraternally (in the Masonic sense) spoke to his father about the meaning of death. In a famous letter, written on 4th April 1787, Wolfgang confided in the dying Leopold: “As death (when closely considered) is the true goal of our life, I have made myself so thoroughly acquainted with this good and faithful friend of man, that not only does its image no longer alarm me, but rather it is something most peaceful and consolatory! And I thank God that He has vouchsafed to grant me the happiness, and has given me the opportunity (you understand me), to learn to see it as the key to our true felicity. I never lie down at night without thinking (young as I am) that I may be no more before the next morning.”

A month later, in the letter dated 11th May of the same year, addressed to his daughter Nannerl, Leopold Mozart voiced his concern: “Your brother is now living at 224, Landstrasse. He has given me no explanation regarding this matter. None at all! Unfortunately, I can guess the reason.” Mozart had already started to get into debt, but what were the reasons and circumstances that had led him to live beyond his means? We can only speculate on the answer to these questions.

On 29th October in Prague he performed his opera Don Giovanni, based on Tirso de Molina’s famous play, in an admirable stage version by Lorenzo Da Ponte, working to instructions from Mozart himself, who wished to give greater prominence to the secondary characters in the quartet, the mask trio, and the sextet. The sublime vision of this opera reveals Mozart as a dramatic genius on a par with Shakespeare or Molière.

In spite of his enormous financial difficulties, his creative energy, encouraged by his success in Prague was not diminished. On the contrary, after the opera he enjoyed a burst of creativity which was to culminate in the composition of his last three symphonies. We agree with Jean-Victor Hocquard, who writes: “He suggests the concept of a vast 3-part symphonic project; it is therefore appropriate not to see these three masterpieces in isolation, but to consider them as the three movements of a single, vast symphonic work.” Mozart the Freemason knew that he was not separate from the universe, and that his own personal story and human society were connected in many ways that were sometimes mysterious and sometimes evident. Like J. & B. Massin, we believe that “It was from his most intimate Erlebnis (experience) that the 1788 trilogy was born, yet it transcends the composer’s personal circumstances while remaining true to them, and the victory proclaimed in the Symphony in C major is both Mozart’s victory over poverty and solitude and the victorious future towards which humanity is progressing.”

This unity strikes us as quite evident, both in terms of performance and as a listening experience: one need only feel the naturalness and eloquence of the development of the first movement of the Symphony in G minor, performing or listening to it after the final Allegro of the Symphony in E-flat major. The same perfect continuity of musical discourse is apparent when we approach the Symphony in C major after the Finale of the Symphony in G minor Hence our proposal of the three symphonies on two CDs, with Symphonies 39 and 40 on CD1 and Symphonies 40 and 41 on CD2. (Repeating the Symphony in G minor on the second CD, enables us to listen to them one after the other, without having to change CDs).

These works, which Mozart possibly never heard performed, were not readily understood in his own day, or even by later generations. At the end of 1790, Gerber published in his Historisch-Biographisches Lexicon der Tonkünstler the following entry on Mozart, referring to his isolation and the difficulty of his contemporaries in understanding his work:

“Thanks to his precocious knowledge of harmony, this great master acquired such a profound and intimate familiarity with this science that it is difficult for an untrained ear to follow his compositions. Even the most seasoned audiences need to listen to his compositions several times.”

Berlioz writes of these last symphonies that they contain “Too many pointless developments to no effect, too many technical tricks”. “If one requires of music an imaginative and impassioned exaltation, sustained and taken to extremes thanks to a rhetoric in which the ‘effects’ are judiciously or obligingly tempered, then he is right”. What is distinctive about Mozart”, argues Jean-Victor Hocquard in his magnificent biography of the composer (Ed. du Seuil, Paris 1970) – “is not only that he did not contrive these effects, but rather that, having tried them, he then broke the mould. His symphonies were unparalleled, and what the maestro had done for the string quartet and quintet, he now achieves in his writing for the orchestra independently of the piano: he makes it the substance of pure poetry.” Mozart reached maturity and the peak of symphonic composition in his day at the age of 32. It was not until eleven years later (1799) that a 29-year-old Ludwig van Beethoven would follow Mozart’s lead and compose his Symphony No. 1 in C major.

———

In 1789 Mozart’s circumstances had deteriorated even further. But what a contrast between the creative intensity of this musical giant and his wretched and increasingly desperate financial situation, one which too often forced him to borrow money from his friends at the Masonic lodge.

In another letter to Michael Puchberg dated 12th July, 1789, he writes:

“Oh, God. Instead of thanking you, I come to you with new requests! Instead of paying off my debts, I come asking for more! If you can see into my heart, you must feel that same anguish that I am experiencing I hardly need remind you that this unfortunate illness is slowing me down with my earnings: however, I must tell you that, in spite of my miserable situation, I decided to go ahead and give subscription concerts at my house so that I can at least meet my numerous current expenses, which are considerable and frequent; for I was absolutely convinced that I could rely on your friendly help and support; but in this respect also I have failed! Unfortunately, fate is so against me, albeit only in Vienna, that I cannot earn any money, no matter how hard I try. For two weeks now I have sent round a list for subscriptions, and the only name on it is Swieten!”

One year later, on 20th January, 1790, Mozart wrote once again to his friend Puchberg:

“If you can and will lend me a further 100 florins, you will oblige me very greatly. We are having the first instrumental rehearsal at the theatre tomorrow. Haydn is coming with me. If your business allows you to do so, and if you would like to hear the rehearsal, please come to my quarters at 10 o’clock tomorrow morning, and we shall all go there together.”

Your very sincere friend.

A. Mozart”

Joseph Haydn and Puchberg followed closely the birth of Così fan tutte, and Puchberg continued to lend Mozart money on the security of the composer’s fees. The premiere took place at the national theatre on 26th January, 1790. The critics’ reactions were good, and it appears that for the first time in Vienna there was unanimity concerning one of Mozart’s operas. The day after the premiere, Mozart celebrated his 34th birthday. It was to be his last full year of life; he would not see out the year 1791. Così fan tutte was performed another four times, but on 20th February Emperor Joseph II died and the theatres remained closed during the official period of mourning until 12th April. For Mozart, Joseph II’s death was a total disaster; the performances of his opera were immediately cancelled and he was unable to organise any concerts. The less immediate consequences were even more serious.

From the end of January until the end of April, he had written nothing – a state of affairs that he had not experienced since the winter of 1779-1780 at Salzburg. It was a clear sign of his depression; he had never been in such dire straits. On 14th August, 1790, he sent Puchberg an S.O.S. – the most tragic of his begging letters.

“My dear friend and brother, I was tolerably well yesterday, but I feel absolutely wretched today: I could not sleep all night because of the pain; I must have got overheated yesterday from walking so much and then I must have caught a chill without realising it. Imagine my situation! Sick and overcome with worries and anguish! Such a situation prevents a quick recovery. In a week or fortnight I shall be better off, certainly, but at present, I am destitute. Could you not help me out with a trifle? The smallest sum would be very welcome just now and for the time being you would provide relief for your true friend and brother.”

A. Mozart”

As Jean and Brigitte Massin so aptly observe in their indispensable book on the life and work of Mozart (Paris 1970): “This time, Mozart had reached rock bottom. That same day, Puchberg sent him 10 florins, the most modest sum he had ever been loaned. This brought Puchberg’s loans to Mozart since those of the previous winter to a total of 510 florins, the composer’s expected fees from Così fan tutte being offered as security. The amounts of money lent by Puchberg closely reflect Mozart’s perceived social standing. In April-May, it seemed likely that Mozart would obtain a coveted position at Court, and Puchberg accordingly answered Wolfgang’s requests by sending him sums of 150 or 100 florins; but when it became clear that he could no longer hope to secure the position, the value of the loans decreased to 10 florins following Mozart’s desperate letter written in August.” Events showed that the increasing distance between the Court of the new Emperor Leopold II and Mozart was due to fear that the French Revolution, which had succeeded in toppling the monarchy of Versailles, would spread, as well as Leopold II’s growing conviction that Freemasons – and particularly those who sympathised with the Enlightenment – were in league with the French Jacobins. Mozart had written the opera The Marriage of Figaro, inspired by the Beaumarchais play of which Louis XVI had said: “For the performance of this play not to be a danger, the Bastille would have to be torn down first.” And he never made any secret of belonging to the Freemasons. Moreover, the most notable among his friends at the lodges were followers of the Enlightenment. “It was unthinkable that the musician who had praised liberty in Die Entführung aus dem Serail, equality in The Marriage of Figaro, and who would go on to raise a hymn to fraternity in The Magic Flute, would not wholeheartedly espouse the slogan “LIBERTY, EQUALITY, FRATERNITY!” that was already familiar to the Grand Orient Lodge of France, and today is proclaimed by revolutionaries.” “The fact that Mozart was not included on the list of the guest musicians at the coronation celebrations was not an oversight or a matter of indifference: it expressed the wish to bury him alive.” (J. & B. Massin).

Towards the end of that grim year of 1790, he received an interesting invitation from the director of the Italian Opera in London to carry out various engagements between December 1790 and June 1791. However, Mozart was not able to accept the offer. To be available at such short notice, he needed to be free of commitments, and Mozart enjoyed no such freedom. His position and his duties prevented him from travelling without making the necessary arrangements to take leave of absence. How was he to sort out such a complicated situation? How was he to find the money necessary to make the trip to England? Mozart was a prisoner of his own hardship, trapped in Vienna. The tour that he had been forced to decline was taken up by one of his closest friends. On 15th December, 1790, Joseph Haydn left Vienna to embark on a London concert tour. After Haydn’s departure, Mozart was once again left to face his financial problems alone. Projects, resolutions, realisations and all his endeavours failed to change the distressed circumstances of his household. His last winter was to prove one of his most difficult: his friend, Joseph Deiner, the owner of the “Zur silbernen Schlange” (The Silver Snake) inn, where Mozart liked to spend time in the company of other musicians, recounted the following: “In 1790, he called on the Mozarts. He found Mozart and his wife in the workroom which overlooked the Rauhensteingasse. The couple were busily dancing around the room. On asking Mozart if he was giving his wife dancing lessons, Mozart laughingly answered: ‘We are warming ourselves up, because we are cold and we can’t afford firewood.” Deiner immediately went and brought some of his own firewood, which Mozart accepted, promising to pay him back as soon as he had some money.” (Joseph Deiner, Memoirs). Ludwig Nohl, Mozart nach den Schilderungen seiner Zeitgenossen, Leipzig, 1880.

In 1791, the Mozart family’s financial circumstances began to improve. Unlike 1790, which had been a disastrous year in which Mozart had composed no works of major importance except the two Prussian Quartets, the String Quintet in D major and his Organ Piece for a Clock – 1791 was one of Mozart’s most prolific years, notably yielding the Piano Concerto No. 27, the Six German Dances for orchestra, the Ave verum corpus, The Magic Flute, La Clemenza di Tito, the Clarinet Concerto in A, Eine kleine Freymaurer-Kantate and the greater part of the Requiem.

On 14th October, 1791, Mozart was in Vienna, and he took Salieri and the latter’s mistress, the singer Caterina Cavalieri, to a performance of The Magic Flute. In his last surviving letter, he wrote to his wife: “Both said that it is an opera worthy to be performed on the greatest occasions before the greatest of monarchs.” That same day, Emperor Leopold II, at the Hofburg Palace in Vienna, received an unsigned letter from a confidant (whose handwriting he recognised), accusing Archduke Franz von Schloissnig, of plotting a revolution against him. One of the ensuing investigations mentioned one of Mozart’s principal patrons, Baron Swieten, as well as many other members of Masonic lodges, whom the Austrian government suspected of wishing to follow France’s example by establishing a constitutional monarchy. There can be little doubt that, as a prominent Freemason, Mozart must also have come under suspicion.

This terrible situation, combined with his delicate state of health and a punishingly intense work schedule, progressively took its toll on his mental and physical condition. The fatal blow came on 12th November, 1791, when a harsh sentence was handed down to Mozart following a trial in which Prince Carl Lichnowsky[2], a member of the same lodge as Mozart during the period 1784-1786, was also involved. Documents discovered by the leading Mozart scholar H. C. Robbins Landon at the Hofkammerarchiv in Vienna concerning a previously unknown court case provide the first evidence of what was probably the chief cause of the composer’s death at the age of 35. They reveal that on 12th November, 1791, Mozart was ordered to repay a debt of 1,435 florins and 32 Kreuzer, as well as 24 florins in costs, involving the embargo of half of his stipend as Imperial-Royal Court Composer and his assets going into receivership. The details of this extraordinary trial are not known, but taking into account Mozart’s extremely precarious situation, it is more than likely that the emotional and financial blow dealt by such an implacable sentence contributed to hasten the composer’s untimely demise. 24 days later, following a grave illness characterised in its later stages by kidney failure, Mozart died at 12.55 a.m. on 5th December, 1791, at the age of 35.

His Freemason brothers organised a funeral ceremony in his memory, and the funeral oration was printed by Ignaz Alberti, a member of the composer’s lodge, who had published the first libretto of The Magic Flute.

At three o’clock in the afternoon of 6th December, 1791, in the afternoon, following a funeral service in the Chapel of the Holy Cross of St. Stephen’s Cathedral, Mozart’s s remains were transferred to St. Mark’s cemetery outside the city walls, where they were buried in a common grave.

_________

“I was for some time quite beside myself over Mozart’s death;

I could not believe that Providence should so quickly have called

an irreplaceable man into the other world.”

Joseph Haydn

When Rossini was asked,

“Who was the greatest musician?” he replied, “Beethoven!”

“And Mozart?” “Oh! He was unique!”

Two hundred years later, this judgment still holds true.

JORDI SAVALL

Melbourne, 28th March, 2019

Translated by Jacqueline Minett

Fast Shipping and Professional Packing

Due to our longstanding partnership with UPS FedEx DHL and other leading international carriers, we are able to provide a range of shipping options. Our warehouse staff are highly trained to pack your goods exactly according to the specifications that we supply. Your goods will undergo a thorough examination and will be safely packaged prior to being sent out. Everyday we deliver hundreds of packages to our customers from all over the world. This is an indication of our dedication to being the largest online retailer worldwide. Warehouses and distribution centers can be located in Europe as well as the USA.

Orders with more than 1 item are assigned processing periods for each item.

Before shipment, all ordered products will be thoroughly inspected. Today, most orders will be shipped within 48 hours. The estimated delivery time is between 3-7 days.

Returns

The stock is constantly changing. It's not entirely managed by us since we are involved with multiple parties such as the factory and our storage. The actual stock can fluctuate at any time. Please understand it may happen that your order will be out of stock when the order is placed.

Our policy is valid for 30 days. If you haven't received your product within 30 days, we're not able to issue either a return or exchange.

You are able to return a product if it is unused and in the same condition when you received it. It must also still remain in the original packaging.

Related products

MUSIC CDS

MUSIC CDS

MUSIC CDS

MUSIC CDS

MUSIC CDS

MUSIC CDS

MUSIC CDS