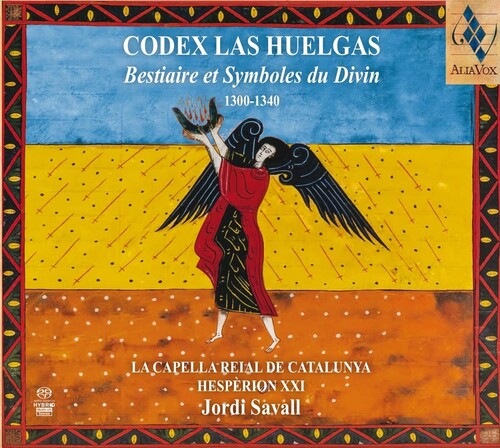

Codex Las Huelgas: Bestiaire et Symboles du Divin – Jordi Savall, LA CAPELLA REIAL DE CATALUNYA, HESPÈRION XXI (2 Hybrid SACDs) ALIA VOX

$ 21,99 $ 13,19

CODEX LAS HUELGAS

Bestiaire et Symboles du Divin

1300-1340

Couvent féminin du Royal Monastère de Santa María de Las Huelgas

Burgos, 1300-1340

Les oracles d’Ézéchiel et les symboles de l’Apocalypse :

L’aigle (Jean), le lion (Marc), le taureau (Lucas) & l’homme (Mathieu)

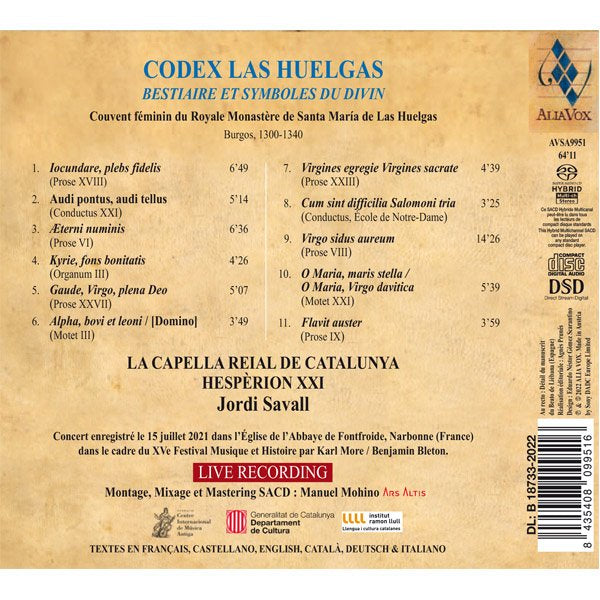

1. Iocundare, plebs fidelis, cuius Pater est in celis 6’49

(Prose XVIII, E-BUlh, Ms 11, nº 67, f. 60)

Le soleil, la lune et les étoiles à la fin du monde.

2. Audi pontus, audi tellus 5’14

(Conductus XXI, E-BUlh, Ms 11, nº 161, f. 167v, 157)

Les mouches abominables éloignées par la Vierge.

3. Æterni numinis 6’36

(Prose VI, E-BUlh, Ms 11, nº 55, f. 38v)

La colombe, symbole du baptême du Christ.

4. Kyrie, fons bonitatis 4’26

(Organum III, E-BUlh, Ms 11, nº 3, f. 2v)

Le Lion, symbole du pouvoir du Christ.

5. Gaude, Virgo, plena Deo 5’07

(Prose XXVII, E-BUlh, Ms 11, nº 76, f. 73v)

L’aigle, le dragon, la brebis, le lion, le serpent, le bœuf, l’agneau et le ver.

6. Alpha, bovi et leoni / [Domino] 3’49

(Motet III, BUlh, Ms 11, nº 83, f. 84v)

Les Vierges prudentes, symbole de pureté et du Temple de l’Esprit Saint.

7. Virgines egregie Virgines sacrate 4’39

(Prose XXIII, E-BUlh, Ms 11, nº 72, f. 67v)

L’aigle, le serpent et le vaisseau passant sans laisser d’empreinte.

8. Cum sint difficilia Salomoni tria 3’25

(Conductus, École de Notre-Dame, F-Pnm Latin 15139 (St Victor), 270v)

L’astre d’or, les bijoux printaniers, roses, violettes, safran et laurier, symbole de la Reine du Ciel.

9. Virgo sidus aureum 14’26

(Prose VIII, E-BUlh, Ms 11, nº 57, f. 41)

Le soleil, la lune et les étoiles, symbole de la lumière de Marie.

10. O Maria, maris stella / O Maria, Virgo davitica / [In veritate] 5’39

(Motet XXI, E-BUlh, Ms 11, nº 104 f. 102v)

L’auster, vent du sud, symbole de lumière claire et brillante.

11. Flavit auster 3’59

(Prose IX, E-BUlh, Ms 11, nº 58 f. 45)

E-BUlh [Hu] Codex Las Huelgas

Versions musicales de Jordi Savall à partir du Manuscrit du Codex Las Huelgas et consultations des transcriptions de Higini Anglès et Juan Carlos Asensio.

LA CAPELLA REIAL DE CATALUNYA

HESPÈRION XXI

Jordi Savall

rebec, vielle d’archet & direction

_

THE BESTIARY AND DIVINE SYMBOLS

Monastery of Santa María la Real de Las Huelgas (Burgos)

The forest of mysticism is not easily penetrated. There are no beaten paths. The last veil of reality cannot be lifted. Mysticism watches and reveals.

Raimon Panikkar

In the monastic life of the Cistercian order, as in the case of the female monastery of Santa María la Real de Las Huelgas (Burgos), a royal pantheon, the seat of coronations and the epicentre of a very intense musical life in which singing played an extremely important part, the nuns were called upon to live a life of simplicity, silence, prayer and contemplation. Flavit auster, which is part of the Las Huelgas Codex, is a Marian text inspired in the Song of Songs in which the most powerful symbols of femininity appear, such as the honeycomb, milk and honey, and protectiveness described as “mother of mercy, port of hope for the shipwrecked and virgin mother purified.” We also find these symbols as early as the 9th century in Islamic and Jewish spirituality where we are taught the nature of the journey within, a path of challenges, knowledge, of the soul’s encounter and union with God. As St Teresa writes, “see this shining castle and this beautiful Oriental pearl, this tree of life which is planted in the very living waters of life.”

Along with this fascinating symbolism of the Queen of Heaven radiant with light among the stars, the golden star, the sun and the moon, as well as the image of milk and honey, flowers, the jewels of Spring, roses, violets, saffron and laurel, in the Las Huelgas Codex we find many animal symbols of Christ, as they were present at the dawn of Christianity. Let us remember the lambs, doves and fish depicted in the frescoes of the early Christian catacombs and Byzantine mosaics. The reality of this world is at once both mystically reflected and veiled. The roots of Christianity are to be found in Platonic teaching, and it was in this philosophical context, which in turn drew on Egyptian and Hindu wisdom, that the new faith was born.

The earliest known Christian bestiary, the Physiologus, was probably written in the 3rd century in Syria. This fundamental text fed the imagination of generations of artists and theologians. The Hispanic Ars antiqua has preserved many works in which animals are allegories of faith which merge with the two- or four-legged companions of medieval man. Alongside basic Marian symbols such as the eagle, the lamb, the fish and, of course, the dove, we find other more surprising creatures such as the “abominable” flies, which traditionally accompany the Prince of Darkness, but also the pelican, a symbol of Christ’s sacrifice, or the dragon, which represented the guardian of the frontiers of the known world. This flame-spitting monster was initially an image of vigilance and ardour before being slain by St George and Siegfried.

It is also in this Codex that we find (in the faux-bourdons of Notre Dame of Paris, and in the pilgrim songs of the Llibre Vermell of Montserrat), the earliest multi-voice songs, the faux-bourdons and the first musical experiments with independent melodies simultaneously sung together. It was the beginning of a true revolution, the Ars nova, which gave rise to a new musical language and which would be masterfully developed by great composers such as Philippe de Vitry and Guillaume de Machaut. At the very moment when national languages were asserting themselves, Ars nova marks the moment at which music became Europe’s true common language.

JORDI SAVALL

Fast Shipping and Professional Packing

Due to our longstanding partnership with UPS FedEx DHL and other leading international carriers, we are able to provide a range of shipping options. Our warehouse staff are highly trained to pack your goods exactly according to the specifications that we supply. Your goods will undergo a thorough examination and will be safely packaged prior to being sent out. Everyday we deliver hundreds of packages to our customers from all over the world. This is an indication of our dedication to being the largest online retailer worldwide. Warehouses and distribution centers can be located in Europe as well as the USA.

Orders with more than 1 item are assigned processing periods for each item.

Before shipment, all ordered products will be thoroughly inspected. Today, most orders will be shipped within 48 hours. The estimated delivery time is between 3-7 days.

Returns

The stock is constantly changing. It's not entirely managed by us since we are involved with multiple parties such as the factory and our storage. The actual stock can fluctuate at any time. Please understand it may happen that your order will be out of stock when the order is placed.

Our policy is valid for 30 days. If you haven't received your product within 30 days, we're not able to issue either a return or exchange.

You are able to return a product if it is unused and in the same condition when you received it. It must also still remain in the original packaging.

Related products

MUSIC CDS

MUSIC CDS

MUSIC CDS

MUSIC CDS

MUSIC CDS

MUSIC CDS

MUSIC CDS