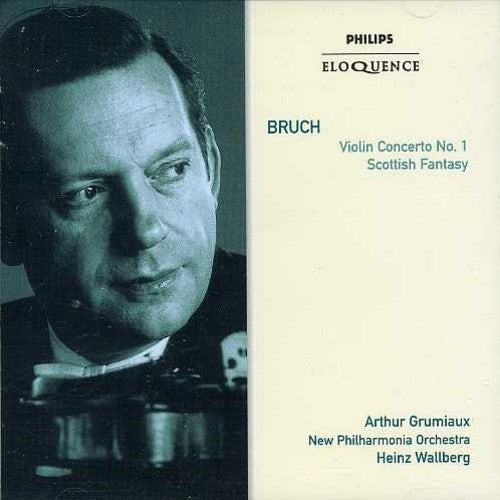

BRUCH: VIOLIN CONCERTO NO. 1; SCOTTISH FANTASY – GRUMIAUX, WALLBERG, NEW PHILHARMONIA DECCA

$ 14,99 $ 8,99

In 1883, Max Bruch boarded a New York-bound steamer departing from Liverpool where he had been working as a conductor. During his American tour, he would conduct various choral societies but biographical material preceded his arrival in New York, making special mention of the first violin concerto: ‘It may well be said that since Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto, no other work of this kind has found and merited such a general friendly recognition’.

The work so caught the public imagination that it eclipsed the two other violin concertos he wrote – as well as a host of other pieces for violin and orchestra – with the exception, of course, of the Scottish Fantasy. The first movement is unusually entitled ‘Vorspiel’ (prelude), and it segues into the heart of the work which lies in the justly famous central ‘Adagio’. The final ‘Allegro energico’, set up with an expectant tremolo in the strings, is Brahmsian in mood – indeed both Bruch’s first and Brahms’ only concertos were composed for the same violinist, Joseph Joachim.

Bruch’s ‘Fantasy Op. 46’ has the full title ‘Fantasia for violin and orchestra with harp, freely using Scottish melodies’; it is by no means an incidental piece but a full-scale concerto in symphonic four-movement form. Like his second violin concerto, it was composed for and dedicated to the violinist Pablo de Sarasate.

It begins in an intransigent E flat minor – in Bruch’s own words, recalling ‘an old bard contemplating a ruined castle, and lamenting the glorious times of old’. The Bardic associations are certainly strengthened by the prominent harp part. By coincidence, the soloist’s opening melody begins identically (except in key and tempo) to that of the first movement of Dvorak’s concerto.

The first of the Scottish folk songs is ‘Auld Rob Morris’, heard in the solo violin over arpeggios in the harp. Although both instruments are characteristic of folk music, Bruch’s rich scoring ensures that the music remains firmly in his own style. The second movement (corresponding the symphonic scherzo) features the folksong ‘Dusty Miller‘; it is first heard over a typically folkloric drone.

There is no break before the third movement, based on the tune ‘I’m down for lack of Johnnie’. It begins in unassuming fashion, low in the soloist’s register with simple harmonies; the soloist then decorates a statement of the tune in the orchestra, leading to another duet with the solo harp.

The finale is marked ‘Allegro guerriero’, and begins with another duet between the two soloists. The harp remains prominent throughout the ensuing set of variations. The marking ‘guerriero’ (warlike) is appropriate. The movement is based on Robert Burns’ song ‘Bruce before Bannockburn’:

Scots, wha hae wi’ Wallace bled,

Scots, wham Bruce has aften led,

Welcome to your gory bed,

Or to victorie…

Lay the proud usurpers low!

Tyrants fall in every foe!

Liberty’s in every blow!

Let us do, or die!

Carl Rosman

‘Playing that is boldly imaginative yet full of subtlety … his rich, beautiful tone and complete technical assurance are unfailingly appealing’ Limelight

‘… melts and yearns with an often aching beauty’ MusicWeb

MAX BRUCH

Violin Concerto No. 1 in G minor, Op. 26

Scottish Fantasy, Op. 46

Arthur Grumiaux, violin

New Philharmonia Orchestra

Heinz Wallberg

Fast Shipping and Professional Packing

Due to our longstanding partnership with UPS FedEx DHL and other leading international carriers, we are able to provide a range of shipping options. Our warehouse staff are highly trained to pack your goods exactly according to the specifications that we supply. Your goods will undergo a thorough examination and will be safely packaged prior to being sent out. Everyday we deliver hundreds of packages to our customers from all over the world. This is an indication of our dedication to being the largest online retailer worldwide. Warehouses and distribution centers can be located in Europe as well as the USA.

Orders with more than 1 item are assigned processing periods for each item.

Before shipment, all ordered products will be thoroughly inspected. Today, most orders will be shipped within 48 hours. The estimated delivery time is between 3-7 days.

Returns

The stock is constantly changing. It's not entirely managed by us since we are involved with multiple parties such as the factory and our storage. The actual stock can fluctuate at any time. Please understand it may happen that your order will be out of stock when the order is placed.

Our policy is valid for 30 days. If you haven't received your product within 30 days, we're not able to issue either a return or exchange.

You are able to return a product if it is unused and in the same condition when you received it. It must also still remain in the original packaging.