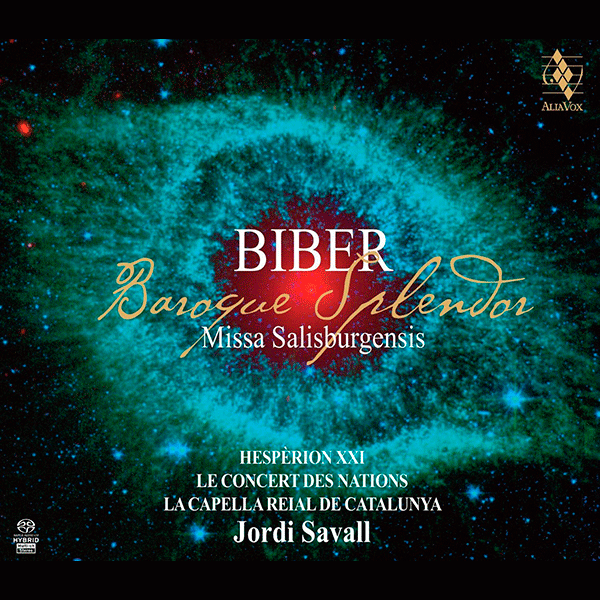

BIBER: BAROQUE SPLENDOR – LE CONCERT DES NATIONS, SAVALL, JORDI ALIA VOX

$ 21,99 $ 13,19

Le Concert des Nations

La Capella Reial de Catalunya

Hespèrion XXI

Direcció: Jordi Savall

Like a great, mysterious nebula, the dazzling Missa Salisburgensis arches over the world of polychoral music by virtue of the exceptional complexity and richness of its means, which are deployed to create a unique expression in sound and space, symbolising with extraordinary exuberance and efficiency all the strength and grandeur of divine power, political and religious power. Shrouded in mystery and regarded by specialists as the Everest of polychoral compositions, this work was discovered by a Salzburg grocer in 1870. At first it was mistakenly attributed to the composer Orazio Benevoli, but now, as Professor Ernst Hintermaier explains (see his accompanying commentary), it is unanimously considered to be among the masterpieces of Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber, one of the greatest and most talented Austrian composers of the Baroque period.

Like a great, mysterious nebula, the dazzling Missa Salisburgensis arches over the world of polychoral music by virtue of the exceptional complexity and richness of its means, which are deployed to create a unique expression in sound and space, symbolising with extraordinary exuberance and efficiency all the strength and grandeur of divine power, political and religious power. Shrouded in mystery and regarded by specialists as the Everest of polychoral compositions, this work was discovered by a Salzburg grocer in 1870. At first it was mistakenly attributed to the composer Orazio Benevoli, but now, as Professor Ernst Hintermaier explains (see his accompanying commentary), it is unanimously considered to be among the masterpieces of Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber, one of the greatest and most talented Austrian composers of the Baroque period.

More than 15 years ago, I was fortunate to have my first experience performing Biber’s sacred music. It was in late May 1999, and I was preparing a concert featuring the Requiem and the Missa Bruxellensis XXIII vocum to be given at Salzburg Cathedral during the Pfingsten Barock Festival. This event provided me with the opportunity to acquire a profound understanding of the complexity of Biber’s polyphonic and polychoral style and, most importantly, to experience it in the acoustic conditions of the cathedral where Biber’s works had received their first public performance during the composer’s lifetime. Thanks to the intense work carried out, we were able to take the opportunity afforded by the concert to make the first live recordings of the Mass as well as the Requiem, two unique versions which we released under our label Alia Vox in 1999 and 2002, respectively.

Fifteen years later, in 2014, we were invited to the Konzerthaus in Vienna during the Resonanzen Festival to perform Biber’s other great Mass, the Missa Salisburgensis à 54 (Vocum), one of the pinnacles of sacred music of all time, and the motet “Plaudite tympana,” which were also composed to mark the 1100th anniversary of the foundation of the archbishopric of Salzburg by St Rupert. To complement the programme we have selected Bartolomaus Riedl’s slightly earlier Fanfares, together with Biber’s Sonata Sancti Polycarpi à 9 and his Battalia à 10, composed in 1673.

The invitation spurred us to prepare the works at home in Catalonia, where we performed them at the Auditori in Barcelona just a few days before the concert at the Konzerthaus in Vienna. We spent several days at Cardona Castle, rehearsing and at the same time working on the sound balance, preparing the recording and experimenting with spatial dispositions in the fine acoustics of the Romanesque chapel. After this period of intense preparation, we gave our first performance of the works at the Auditori in Barcelona on 15th January 2015. On 16th January we returned to Cardona for a final recording session before leaving the next day for Vienna, where on 18th January we performed the complete programme for a second time at the city’s Konzerthaus.

Despite our intense experience of performing Biber at Salzburg Cathedral in 1999, and taking into account the complexity of Biber’s polyphonic music, I must confess that I approached the preparation of the Missa Salisburgensis with a great deal of respect and the utmost care in relation to the exceptionally large number of parts (54) to be kept under control, bringing out the music’s extremely complex counterpoints and, above all, the conditions necessary to achieve the right spatial balance in the layout of the various, highly contrasting ensembles or choruses of voices and instruments so clearly envisaged by the composer himself:

Chorus 1. 8 soloist Voices in concert and Organ

Chorus 2. 6 Strings [2 Violins, 2 Violas, 2 Viols]Chorus 3. 2 Oboes, 4 Flutes [2 Flutes, 2 Dulcians], 2 Clarino trumpets

Chorus 4. 2 Cornetti, 3 Trombones)

Chorus 5. 8 soloist Voices in concert[Chorus 6.] 6 Strings [2 Violins, 2 Violas, 2 Viols]1. Loco. 4 Trumpets, Timpani

2. Loco. 4 Trumpets, Timpani

Organ

Basso Continuo (Cello and Violone)

This exceptional line-up serves to remind us that the archbishopric of Salzburg was one of the leading centres of the ancient Roman and Venetian traditions. Having embraced them, it then went on to transmit them after embellishing them in many respects. The vast acoustics of Salzburg Cathedral demanded a style that avoided excessively rapid harmonic changes and highly individual ornamental refinements.

On first hearing the work, therefore, one might be surprised by the inevitable, dominating presence of the C major key of the trumpets; however, as Paul McCreesh (the founder and director of the Gabrieli Consort & Players) observed, on listening more carefully we discover a very subtle structure and some surprising harmonic shifts, which are all the more remarkable in that they occur during a sumptuous pasaje in C major, as well as a rich abundance of motifs in the ground bass. A simple, popular musical figure features in the development of much of the melodic material, as well as the novel effects in the Benedictus and the Agnus Dei, with its poignant a capella polyphony in the Miserere and especially the great richness of figures which unfold in the Gloria in excelsis Deo and the Credo. We are enthralled by the breathtaking emotion and guileless beauty of the Incarnatus, sung by the six high voices, and, in stark contrast, the deep sorrow conveyed by the Crucifixus, sung exclusively by the deep voices.

For the recording we positioned the various choruses in the chapel of Cardona Castle so as to recreate the same spatial conditions and instrumental layout used in Salzburg Cathedral: Basso continuo (cello and violone) in the centre, flanked on either side by the two choirs of voices in concerto (choruses 1 and 5), consisting of 8 solo voices, each one accompanied by an organ; opposite and mirroring each other, the two string ensembles (choruses 2 and 6); behind the vocal ensembles, to the right, 2 cornetti and 3 sackbuts (chorus 4) in an allusion to Venice, and to the left 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 dulcians and 2 clarini (chorus 3), which are distinguished by their flexibility and high-pitched harmonics from the more military sound provided by the two choruses of trumpets and timpani (Loco 1 and 2), which are placed at either end of the church (at the altar and at the far end of the building) to provide a powerful punctuation to the various sections of the Mass and the Motet. These instrumental ensembles link heaven and earth: blazing fanfares to the glory of God, celebrating the power and magnificence of an ancient church and a city-state at the core of political power in a country at the German heart of the old Holy Roman Empire of central Europe.

Difficult though it is to imagine how the people of Salzburg might have reacted to this truly stunning “musical nebula” in 1682, it seems likely, as Reinhard Goebel (the founder and director of Musica Antiqua Köln) speculated, “that they were undoubtedly as moved and spellbound as we – and in particular, we, the performing musicians – are today.” Whatever the case may be, this music demonstrates that Salzburg had nothing to envy Rome or Venice. The Baroque splendour of the archbishopric calls to mind the symbolic image of the heavenly Jerusalem, with its myriad spires and hosts of cherubim singing the eternal praises of a heavenly life bearing a new message of peace and the promise of universal redemption.

JORDI SAVALL

Fast Shipping and Professional Packing

Due to our longstanding partnership with UPS FedEx DHL and other leading international carriers, we are able to provide a range of shipping options. Our warehouse staff are highly trained to pack your goods exactly according to the specifications that we supply. Your goods will undergo a thorough examination and will be safely packaged prior to being sent out. Everyday we deliver hundreds of packages to our customers from all over the world. This is an indication of our dedication to being the largest online retailer worldwide. Warehouses and distribution centers can be located in Europe as well as the USA.

Orders with more than 1 item are assigned processing periods for each item.

Before shipment, all ordered products will be thoroughly inspected. Today, most orders will be shipped within 48 hours. The estimated delivery time is between 3-7 days.

Returns

The stock is constantly changing. It's not entirely managed by us since we are involved with multiple parties such as the factory and our storage. The actual stock can fluctuate at any time. Please understand it may happen that your order will be out of stock when the order is placed.

Our policy is valid for 30 days. If you haven't received your product within 30 days, we're not able to issue either a return or exchange.

You are able to return a product if it is unused and in the same condition when you received it. It must also still remain in the original packaging.