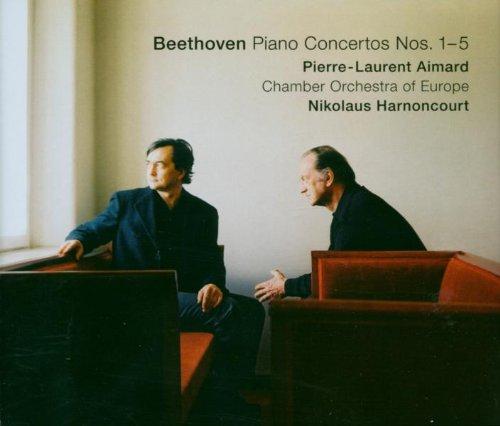

BEETHOVEN : PIANO CONCERTOS NO 1-5 (COMPLETE) – AIMARD, HARNONCOURT, CHAMBER ORCHESTRA OF EUROPE (3CDS) WARNER CLASSICS

$ 29,99 $ 17,99

“The freshness of this set is remarkable. You do not have to listen far to be swept up by its spirit of renewal and discovery, and in Pierre-Laurent Aimard as soloist Harnoncourt has made an inspired choice. Theirs aren’t eccentric readings of these old warhorses – far from it. But they could be called idiosyncratic – from Harnoncourt would you have expected anything else? These are modern performances which have acquired richness and some of their focus from curiosity about playing styles and sound production of the past. Harnoncourt favours leaner string textures than the norm and gets his players in the excellent COE to command a wide range of expressive weight and accent; this they do with an immediacy of effect that’s striking. Yet there’s a satisfying body to the string sound, too.

The playing seems to have recourse to eloquence without having to strive for it, and that’s characteristic of Aimard’s contribution as well. Strong contrasts are explored and big moments encompassed as part of an unforced continuity in which nothing is hurried. The big moments do indeed stand out: one of them is the famous exchange of dramatic gestures between piano and orchestra in the development of the E flat Concerto’s (No 5’s) first movement; another the equally dramatic but very different exchange when the piano re-enters at the start of the development in the first movement of the G major Concerto (No 4). At these junctures, conductor and pianist allow the gestures to disrupt the rhythmic continuity. Over the top? No, but risky maybe, and if you’ve strong views about what Beethoven’s rubrics permit, or have swallowed a metronome, you may react strongly. For make no mistake, Aimard is as intrepid an explorer here as Harnoncourt – by conviction, not simply by adoption.

Technically he’s superbly equipped. This is evident everywhere, but especially in the finales, brimful of spontaneous touches and delight in their eventfulness and in the pleasure of playing them. The finale of the Emperor tingles with a continuously vital, constantly modulated dynamic life that it rarely receives; so many players make it merely rousing. And among the first movements, that of the G major Concerto is a quite exceptional achievement for the way Harnoncourt and his soloist find space for the fullest characterisation of the lyricism and diversity of the solo part – Aimard begins almost as if improvising the opening statement, outside time – while integrating these qualities with the larger scheme.

It’s the most complex movement in the concertos and he manages to make it sound both directional and free as a bird.

The first movement of the E flat Concerto is nearly as good, lacking only the all-seeing vision and authority Brendel brings to it, and perhaps a touch of Brendel’s ability to inhabit and define its remoter regions. In general, Aimard imposes himself as a personality less than Brendel. In spite of being different exercises, their distinction touches at several points and is comparable in degree. What Aimard doesn’t match is the variety of sound and the amplitude of Brendel’s expressiveness in the first two concertos’ slow movements. Balances are good, with the piano placed in a concerthall perspective.

This set balances imagination and rigour, providing much delight and refreshment, and playing that will blow you away.â€

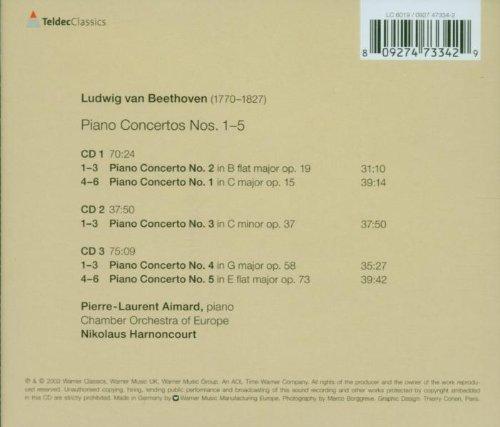

Beethoven: Piano Concertos Nos. 1-5 (complete)

Pierre-Laurent Aimard (piano)

Chamber Orchestra of Europe, Nikolaus Harnoncourt

Â

| COMPOSER | BEETHOVEN, LUDWIG VAN |

|---|---|

| NUMBER OF CDS | 3 |

| PERFORMER | HARNONCOURT, AIMARD |

Fast Shipping and Professional Packing

Due to our longstanding partnership with UPS FedEx DHL and other leading international carriers, we are able to provide a range of shipping options. Our warehouse staff are highly trained to pack your goods exactly according to the specifications that we supply. Your goods will undergo a thorough examination and will be safely packaged prior to being sent out. Everyday we deliver hundreds of packages to our customers from all over the world. This is an indication of our dedication to being the largest online retailer worldwide. Warehouses and distribution centers can be located in Europe as well as the USA.

Orders with more than 1 item are assigned processing periods for each item.

Before shipment, all ordered products will be thoroughly inspected. Today, most orders will be shipped within 48 hours. The estimated delivery time is between 3-7 days.

Returns

The stock is constantly changing. It's not entirely managed by us since we are involved with multiple parties such as the factory and our storage. The actual stock can fluctuate at any time. Please understand it may happen that your order will be out of stock when the order is placed.

Our policy is valid for 30 days. If you haven't received your product within 30 days, we're not able to issue either a return or exchange.

You are able to return a product if it is unused and in the same condition when you received it. It must also still remain in the original packaging.