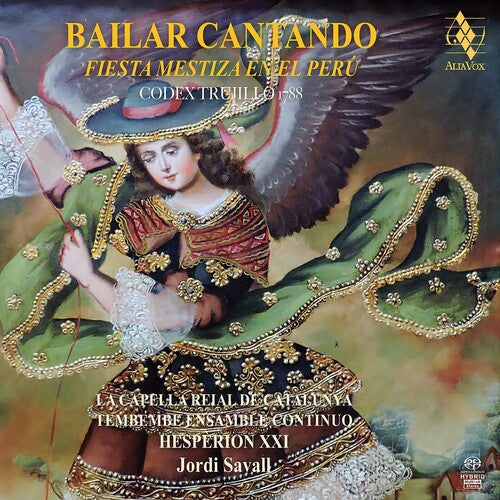

BAILAR CANTANDO: Fiesta Mestiza En El Peru – SAVALL, Hesperion XX (Hybrid SACD) ALIA VOX

$ 21,99 $ 13,19

The twenty pieces comprising the musical collection in the Codex Trujillo del Perú are an exceptional case in the history of the indigenous music of the New World. This collection of tonadas, cachuas, tonadillas, bayles, cachuytas and lanchas offers a glimpse of the repertory native to the traditions of the country, as indicated by the text of one of the cachuas sung “al uso de nuestra tierra” (“according to the customs of our land”) and in particular the songs and dances favoured by the popular classes who lived in the “Viceroyalty of Peru” at the end of the 18th century.

“No one listening to these sweetly elegant pieces would bother themselves with their historical context for long, so winning is their timeless South American spirit – a benign mixture of Spanish, Amerindian and African aesthetics … Savall’s orchestrations…sound just the part, as does the stylish singing, and although there isn’t any dancing it certainly isn’t hard to visualise some … it all sounds like a gently joyous occasion, like some long-remembered summer night under the stars. Irresistible.”

Lindsay Kemp – Gramophone, November 2018

DANCING AND SINGING

MESTIZO FESTIVITY IN PERU

Codex Trujillo, ca. 1780

The twenty pieces comprising the musical collection in the Codex Trujillo del Perú are an exceptional case in the history of the indigenous music of the New World. This collection of tonadas, cachuas, tonadillas, bayles, cachuytas and lanchas offers a glimpse of the repertory native to the traditions of the country, as indicated by the text of one of the cachuas sung “al uso de nuestra tierra” (“according to the customs of our land”) and in particular the songs and dances favoured by the popular classes who lived in the “Viceroyalty of Peru” at the end of the 18th century.

The vast majority of the songs are tonadas or chansons intended to be danced and sung (“para baylar cantando”), and although most of the texts are in Spanish, displaying the characteristic variants of Spanish as it was spoken by the native Indians, the collection also includes texts in Quechua and Mochica, which – like the music itself – show a clear relationship with the indigenous cultures of Indian and African origin. All these elements explain the highly distinctive style of these “native songs” which clearly sets them apart from the music of Spain and that of the New World. They have been handed down to us by composers of the same period who were active at court or in the major churches of the Viceroyalty of Peru.

Without wishing to restrict the original meaning of the word “mestizo”, we have subtitled our selection “Fiesta mestiza en el Perú [Mestizo festivity in Peru]” to underline the symbiosis between the local and Hispanic traditions and the influence of native Indian peoples and the Africans transported from Africa as a result of the slave trade. In our imaginary symbolic celebrations featuring this wonderful collection of music dating from ca. 1780, we bring together all shades of the various racial and social groups who lived side by side in the amazingly rich and highly stratified society of the Viceroyalty of Peru. These included the Spaniards and Creoles (mainly White, but also some Africans born in America) at the top of the social ladder, as well as the different native Indian communities, the mestizos (of mixed Indian and white European descent, or vice versa), and the African blacks (who had arrived as slaves) and the mulattos (of mixed white and black parentage).

By the time the Spanish arrived in Peru with Francisco Pizarro (1532), the original native Indian population had witnessed for more than 2000 years cultures as rich as those of the Nazcas, Tiahuanacos, Chimús and Chinchas. Musical practices in the second half of the 17th century were therefore the result of a long dialogue between local traditions and the likely influence of and ultimate fusion with foreign inputs, whether Iberian or African. Finally, even though it is possible to detect certain influences in terms of harmony, rhythm, melody and instrumentation of the Spanish or European musical traditions (mainly those brought by the musicians who had accompanied the Conquistadors), the repertory of the Codex Trujillo is remarkably faithful to what we regard as a perfect synthesis of a popular style peculiar to the local traditions. This hypothesis is confirmed when we consider the unique originality of the “sung dances” and the few similarities linking them to the Iberian and South American repertories of the 17th and 18th centuries. This is all the more evident when we examine the 1411 watercolours contained in the Codex, and particularly 36 illustrations depicting musicians with their instruments and costumes and the choreographies of each dance, which chronicle the true history of the folk music traditions of colonial Peru and reveal the missing link between the ancient music of the New World and its traditional repertory that remains so extraordinarily vibrant today.

We came across this collection many years ago, but it was not until 2002, when we were preparing our new programmes based on the Villancicos criollos and the Folias Criollas (Alia Vox no. AV9834), that we performed two of the cachuas para baylar cantando. We were immediately surprised and fascinated by the essential distinctiveness of the repertory, but it was precisely that distinct quality which made it necessary for us to take time to study it and fully appreciate its special character. It is a unique and documented example of a popular tradition of 18th century colonial Peru.

Before mentioning our recent and fruitful collaborations, I would like to pay tribute here to Lorenzo Alpert and Gabriel Garrido, two magnificent Argentinian musicians whom I met when I was a student at Basel (1968-1970) and later as a teacher (from 1974) in my Chamber Music class at the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis. It was while working with them on Renaissance and Hispanic Baroque music that I began to appreciate the true value of certain South American traditions and the similarities between them, especially in their use of the characteristic percussion rhythms and Baroque guitar “rasgueados”. A few months later, Montserrat Figueras (voice), Hopkinson Smith (lute, vihuela de mano and guitar) and I founded Hespèrion XX with the collaboration of Lorenzo Alpert (flutes and percussion) and Gabriel Garrido (flutes, guitar and percussion). Subsequently, each one pursued his or her own career: Lorenzo Alpert became a virtuoso Baroque bassoonist, and in 1981 Gabriel Garrido founded the Ensemble Elyma, with whom he has built up an extraordinary output, notably in the South American repertories.

But let us return to the 21st century. In 2006 another providential meeting took place. Following an invitation from the Festival Cervantino de Guanajuato to perform a concert with a Mexican ensemble as part of a tribute to Catalonia, I proposed a programme in conjunction with the Tembembe Ensamble Continuo. I happened to be familiar with the work of this group thanks to some recordings I had received from a film producer who wanted me to provide the soundtrack for a film set in Mexico during the Baroque period. It was through the involvement of these extraordinary musicians and their expert knowledge of folk traditions, and the ensemble that they formed with the soloists of La Capella Reial de Catalunya and Hespèrion XXI, that I began to envisage the possibility of performing the pieces in the Codex, because they guaranteed the works’ essential spirit and style, which is both popular and refined, historical and yet very much alive in the present.

In 2010 we started to work on the whole collection with a view to performing it in concert. A few years later in 2013 (Providence steps in once more!), I received from the musicologist and musician Adrián Rodríguez van der Spoel, as a personal gift – and I would like to take this opportunity to express to him my warmest thanks and congratulations – a copy of the volume containing his extraordinary research on the Codex Trujillo. His book Bailes, Tonadas & Cachuas · La Música del Códice Trujillo del Perú en el siglo XVIII (published by deuss music, The Hague in 2013) is a meticulous and well-documented study that I wholeheartedly recommend to anybody wishing to acquire a deeper understanding of the work and its period.

Adrián Rodríguez’s study on the Codex Trujillo, which showcases all the existing knowledge about the music in this extraordinary collection, has enabled us to further our own research on the original manuscript, which has provided the basis for our study and performance. Finally, in January 2015, we performed our first complete version of the collection during various concerts given at the Festival de Cartagena de las Indias in Colombia on the theme “The Music of the New World”. A year and a half later, in July 2017, we again performed the concert at the Festival de l’Abbaye de Fontfroide in France and the Styriarte Festival in Graz, Austria, when we also made the present recording thanks to the artistry of our sound engineer, Manuel Mohino.

The music of the Codex Trujillo, preserved thanks to the recompilation overseen by Bishop Baltasar Jaime Martínez Compañón, an illustrious representative of that “enlightened despotism” which characterised the reign of King Charles III of Spain, constitutes a magnificent example of the artistic and human strength of a people who, despite ruthless colonial exploitation and centuries of suffering (which in some cases still persists to this day) sought to salvage their dignity and a ray of hope through the joy of music and dance.

The inexhaustible energy and exotic charm of the rhythms and age-old melodies featured in “Fiesta mestiza en el Perú” are undeniable proof that the creative impulse of ordinary people never fails to produce wonderful music whose beauty, emotion and joy continue to speak to us today with all the vitality and poetry of the living moment.

JORDI SAVALL

Fast Shipping and Professional Packing

Due to our longstanding partnership with UPS FedEx DHL and other leading international carriers, we are able to provide a range of shipping options. Our warehouse staff are highly trained to pack your goods exactly according to the specifications that we supply. Your goods will undergo a thorough examination and will be safely packaged prior to being sent out. Everyday we deliver hundreds of packages to our customers from all over the world. This is an indication of our dedication to being the largest online retailer worldwide. Warehouses and distribution centers can be located in Europe as well as the USA.

Orders with more than 1 item are assigned processing periods for each item.

Before shipment, all ordered products will be thoroughly inspected. Today, most orders will be shipped within 48 hours. The estimated delivery time is between 3-7 days.

Returns

The stock is constantly changing. It's not entirely managed by us since we are involved with multiple parties such as the factory and our storage. The actual stock can fluctuate at any time. Please understand it may happen that your order will be out of stock when the order is placed.

Our policy is valid for 30 days. If you haven't received your product within 30 days, we're not able to issue either a return or exchange.

You are able to return a product if it is unused and in the same condition when you received it. It must also still remain in the original packaging.

Related products

MUSIC CDS

MUSIC CDS

MUSIC CDS

MUSIC CDS

MUSIC CDS

MUSIC CDS