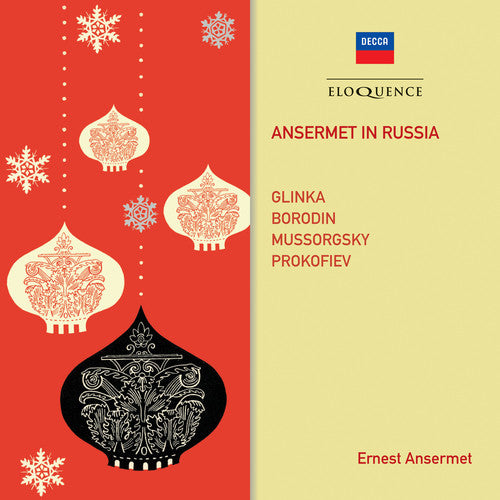

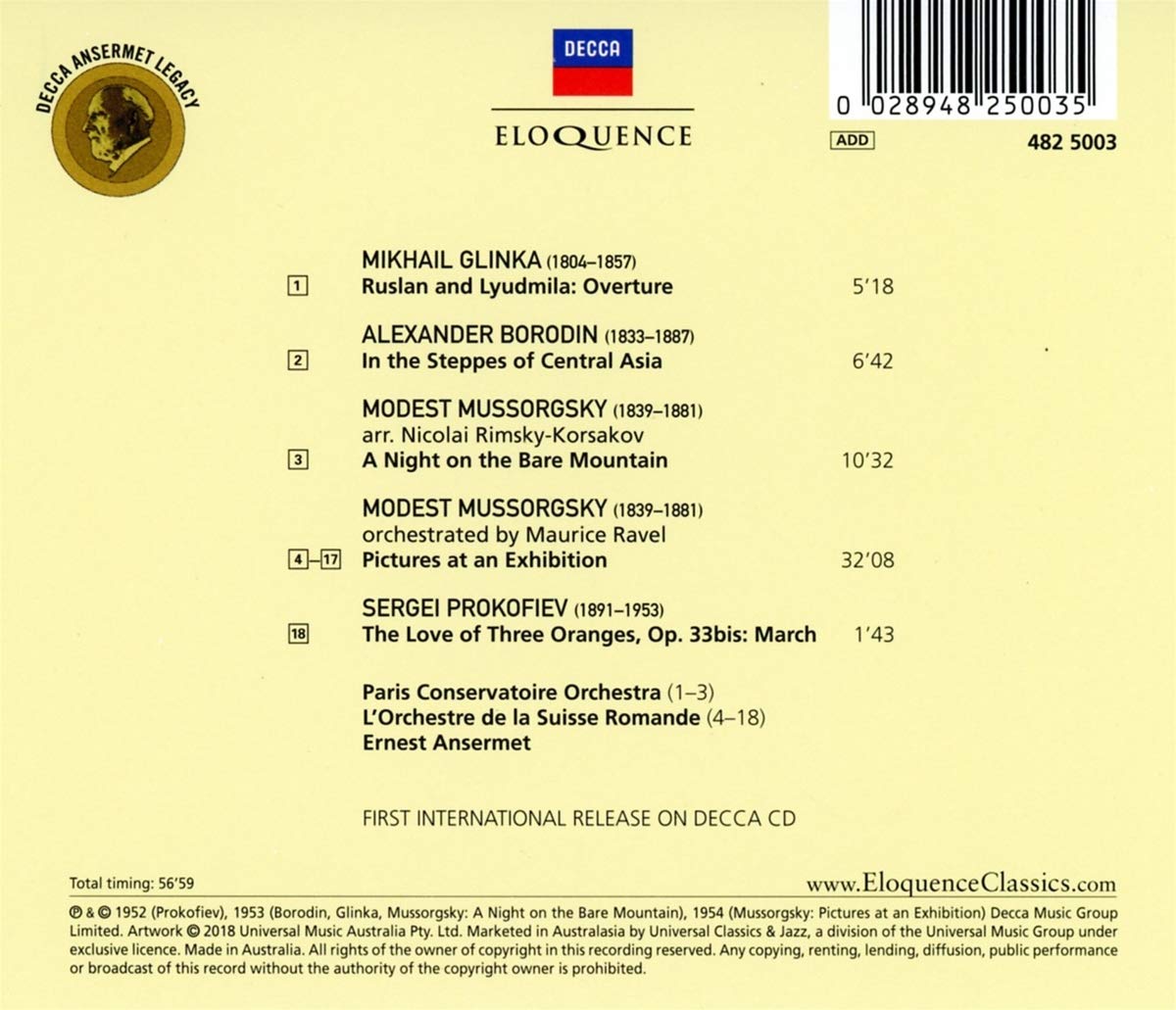

ANSERMET IN RUSSIA (GLINKA, BORODIN, MUSSORGSKY, PROKOFIEV) DECCA

$ 6,99 $ 4,19

Russian music was always a fundamental part of Ansermet’s vast repertoire. Of course, he spent seven years as conductor with the famous Ballets Russes during a particularly glorious period for the company. Formed in 1907 by Serge Diaghilev, the Ballets Russes brought a breath of fresh air to artistic creativity at the beginning of the twentieth century and had a decisive influence on the tastes and customs of the countries through which the company travelled. Under the leadership of the cultivated and somewhat capricious Diaghilev, the Ballets Russes went on to discover and encourage new choreographers (Fokine, Nijinsky, Massine, Balanchine, Lifar) who made a lasting impact on the history of modern dance while at the same time putting its faith in new creative artists, dancers and composers (Stravinsky, Ravel, Poulenc, Milhaud), writers (Cocteau) and painters (Bakst, Larionov, Braque, Picasso, de Chirico, Delaunay, Matisse, Laurencin and many others).

Numerous conductors worked with the Ballets Russes and while some have been forgotten, others are still very much remembered – such as Pierre Monteux (who gave the first performance of ‘The Rite of Spring’, among other works) and particularly Ansermet who, from 1916 to 1923, was in the company’s front line, conducting the first performances of such famous ballets as Satie’s ‘Parade’, Falla’s ‘Three-Cornered Hat’, Stravinsky’s ‘Song of the Nightingale’, ‘Pulcinella’, ‘Renard’ and ‘Les Noces’ and Prokofiev’s ‘Chout’.

But Ansermet knew and loved Russian music quite apart from the Ballets Russes. The Europe that was pre-World War I had a strong attachment to this music. Glinka’s overture to ‘Ruslan and Lyudmila’, Rimsky-Korsakov’s ‘Scheherazade’, ‘Golden Cockerel’ and’ Antar’, Mussorgsky’s ‘A Night on the Bare Mountain’, and Borodin’s ‘In the Steppes of Central Asia’, ‘Polovtsian Dances’ and Second Symphony were some of the regulars at the Sunday concerts of the great European orchestral associations. It was Ravel, a devotee of recent Russian music who proposed the first movement of Borodin’s Second Symphony as the rallying cry of the ‘Société des Apaches’, a French artistic group formed in 1900, principally of musicians and writers. Ravel dedicated each of the pieces in his ‘Miroirs’ for piano to a member of the Apaches. It should not be forgotten, too, how much of Mussorgsky’s ‘Boris Godunov’ rubbed off on Debussy’s ‘Pelléas et Mélisande’ or that the composer had, as a young man, been the piano-teacher of the children of Tchaikovsky’s patroness, Nadezhda von Meck.

Russian music consequently held no mysteries for Ansermet, and with his long black beard, he was even taken for a Russian on occasion. The conductor loved to tell the tale of how, after a performance by the Ballets Russes in Madrid in the presence of Alfonso XIII, the King had said to him, ‘So obviously, with your beard, you are a complete Muscovite!’ and Ansermet replied, ‘No, Your Majesty, I’m Swiss!’. The King proceeded to slap his thighs with amusement that a Swiss was conducting the Russian ballet.

Russian repertoire accounts for a large part of Ansermet’s discography, starting in New York in 1916 with extracts from works by Rimsky-Korsakov (‘Scheherazade’ and ‘The Snow Maiden’), Nikolai Tcherepnin (‘Le Pavillon d’Armide’) and ending in 1968 with the sumptuous recording with the New Philharmonia Orchestra of the complete ‘Firebird’ ballet by Stravinsky, in the original 1910 version. In between, Ansermet made many recordings of Russian repertoire, including Tchaikovsky’s three great ballets, the ‘Pathétique’ Symphony and other works. Other Russian composers included Borodin, Rimsky-Korsakov, Balakirev, Glazunov, Liadov, Rachmaninov, Prokofiev and, in first place of course, Stravinsky; Ansermet remains one of the major interpreters of his music. It is a source of joy but also, at times, confusion that the same works were recorded several times, as recording technology developed. What is striking is that Ansermet’s interpretations vary little from one version to another – which is not to say that he did not develop as an artist but rather that he was a conductor with a matured and considered concept of the work he was performing.

This collection brings together Russian repertoire recorded at the very beginning of the 1950s, just before the invention of stereo.

MIKHAIL GLINKA

Ruslan and Lyudmila: Overture

ALEXANDER BORODIN

In the Steppes of Central Asia

MODEST MUSSORGSKY

arr. Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov

A Night on the Bare Mountain

MODEST MUSSORGSKY

orchestrated by Maurice Ravel

Pictures at an Exhibition

SERGEI PROKOFIEV

The Love of Three Oranges, Op. 33bis: March

Paris Conservatoire Orchestra

L’Orchestre de la Suisse Romande

Ernest Ansermet

Fast Shipping and Professional Packing

Due to our longstanding partnership with UPS FedEx DHL and other leading international carriers, we are able to provide a range of shipping options. Our warehouse staff are highly trained to pack your goods exactly according to the specifications that we supply. Your goods will undergo a thorough examination and will be safely packaged prior to being sent out. Everyday we deliver hundreds of packages to our customers from all over the world. This is an indication of our dedication to being the largest online retailer worldwide. Warehouses and distribution centers can be located in Europe as well as the USA.

Orders with more than 1 item are assigned processing periods for each item.

Before shipment, all ordered products will be thoroughly inspected. Today, most orders will be shipped within 48 hours. The estimated delivery time is between 3-7 days.

Returns

The stock is constantly changing. It's not entirely managed by us since we are involved with multiple parties such as the factory and our storage. The actual stock can fluctuate at any time. Please understand it may happen that your order will be out of stock when the order is placed.

Our policy is valid for 30 days. If you haven't received your product within 30 days, we're not able to issue either a return or exchange.

You are able to return a product if it is unused and in the same condition when you received it. It must also still remain in the original packaging.