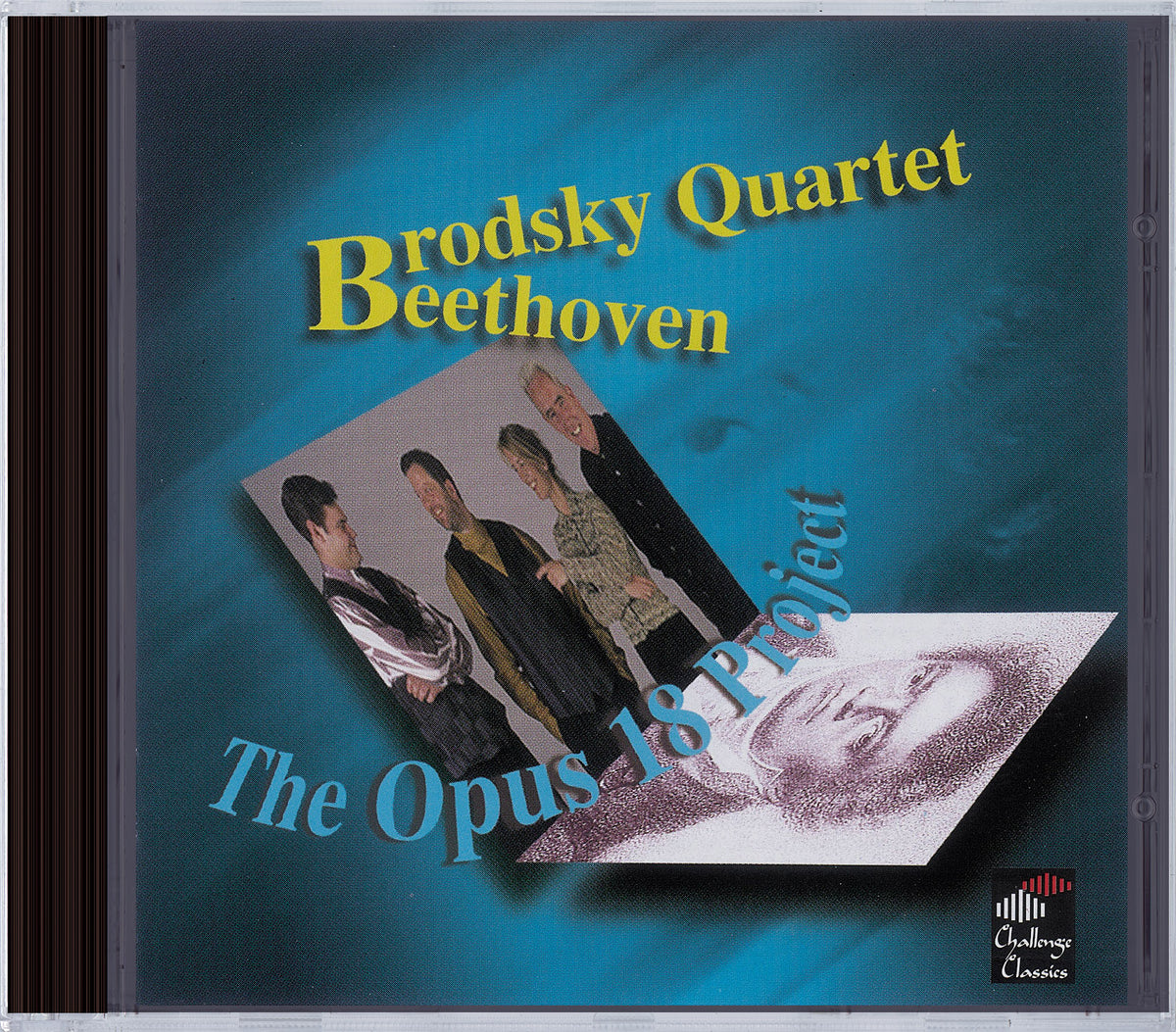

BEETHOVEN: THE OPUS 18 PROJECT – BRODSKY QUARTET (3 CDS) CHALLENGE

$ 2,99 $ 1,79

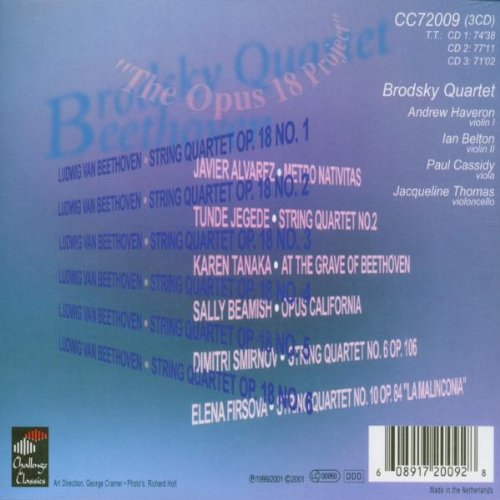

Disc #1

01. String Quartet, Op. 18, No. 1 in F Major: I. Allegro con Brio 09:28

02. String Quartet, Op. 18, No. 1 in F Major: II. Adagio Affettuoso Ed Appassionato 09:58

03. String Quartet, Op. 18, No. 1 in F Major : III. Scherzo (Allegro Molto) & Trio 03:26

04. String Quartet, Op. 18, No. 1 in F Major:: IV. Allegro 06:11

05. Metro Nativitas 08:46

06. String Quartet, Op. 18, No. 2 in G Major: I. Allegro 07:50

07. String Quartet, Op. 18, No. 2 in G Major : II. Adagio Cantabile 06:16

08. String Quartet, Op. 18, No. 2 in G Major: III. Scherzo (Allegro) & Trio 04:36

09. String Quartet, Op. 18, No. 2 in G Major: IV. Allegro molto Quasi Presto 05:43

10. String Quartet No. 2 12:16

Disc #2

01. String Quartet, Op. 18, No. 3 in D Major: I. Allegro 08:30

02. String Quartet, Op. 18, No. 3 in D Major: II. Andante con Moto 08:12

03. String Quartet, Op. 18, No. 3 in D Major : III. Allegro 02:47

04. String Quartet, Op. 18, No. 3 in D Major: IV. Presto 05:39

05. At the Grave of Beethoven: I. – 04:17

06. At the Grave of Beethoven: II. – 05:22

07. String Quartet, Op. 18, No. 4 in C Minor : I. Allegro Ma non Tanto 09:28

08. String Quartet, Op. 18, No. 4 in C Minor : II. Scherzo (Andante Scherzoso QuasI. Allegretto) 06:34

09. String Quartet, Op. 18, No. 4 in C Minor: III. Menuetto (Allegretto) & Trio 04:30

10. String Quartet, Op. 18, No. 4 in C Minor : IV. Allegro 04:17

11. Opus California: I. Boardwalk 02:08

12. Opus California: II. Golden Gate 03:39

13. Opus California: III. Dreams Before Lullaby’s 02:53

14. Opus California: IV. Natural Bridges 02:39

Disc #3

01. String Quartet, Op. 18, No. 5 in A Major: I. Allegro 06:38

02. String Quartet, Op. 18, No. 5 in A Major: II. Menuetto & Trio 05:26

03. String Quartet, Op. 18, No. 5 in A Major: III. Andante Cantabile 09:59

04. String Quartet, Op. 18, No. 5 in A Major: IV. Allegro 06:58

05. String Quartet No. 6, Op. 106: I. Serenata Notturna 04:31

06. String Quartet No. 6, Op. 106: II. ‘Un Ballo in Maschera’ or ‘Aufforderung Zum Tanz’ 08:37

07. String Quartet, Op. 18, No. 6 in B-Flat Major: I. Allegro con Brio 06:12

08. String Quartet, Op. 18, No. 6 in B-Flat Major: II. Adagio Ma non Troppo 07:35

09. String Quartet, Op. 18, No. 6 in B-Flat Major: III. Scherzo (Allegro) & Trio 03:25

10. String Quartet, Op. 18, No. 6 in B-Flat Major: IV. Adagio (La Malinconia): Allegretto Quasi Allegro 08:21

11. La Malinconia, String Quartet No. 10, Op. 84 09:22

Although the whole Op. 18 set of string quartets was dedicated to Prince Lobkowitz, a loyal and enthusiastic patron of Beethoven, an earlier version of the Op. 18, No. 1 quartet existed and was dedicated to Beethoven’s friend, Karl Amenda. Amenda was a theologian and violinist who made Beethoven’s acquaintance in Vienna. Apparently, Beethoven was unhappy with his first version of the quartet and wrote Amenda a letter requesting that the piece not be shown to or played by anyone. He added that he had a lot to learn about quartet writing and had finished a new version of the piece.

The No. 1 quartet exists in four movements, the first of which is an Allegro con brio. Although there are parts that are quick and spirited, they are mixed with many lyrical qualities as well. The opening motive, centering in on the pitch of F with a melodic turn, is an important one, as it returns in various ways throughout the movement. The music takes on a more fiery character in the development where the key turns to minor before working itself back into the opening motive and its various inventive (and sometimes surprising) manifestations to bring the movement to a close.

Beethoven’s sketches show that he composed the second movement, an Adagio, with the intention to depict the tomb scene from Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. Beethoven’s markings for the movement read Adagio affetuoso ed appassionato, and this emotion comes to the fore immediately with the opening violin melody which sings out over a pulse of moving triplets in the other instruments. The melody returns again in the cello and is developed in a bittersweet manner, moving for a time from the minor key into major. There is a stormy development before the melody returns, this time over a much more agitated accompaniment. Beethoven’s use of silence between high-tension chords is original and has great dramatic appeal.

The third movement is a clever and playful Scherzo whose uneven phrase structures and boisterous accents provide a feeling of surprise and jocularity. In the trio section the first violin is kept busy with numerous brilliant passages.

The final movement is a pleasant Allegro that, similarly to the first movement, develops the opening motive in many creative ways. This motive, which is introduced by the violin, is built on a sequence of fast-moving triplets, the effect of which is especially virtuosic.

Beethoven wrote his Op. 18, No. 2 string quartet in G major between the years of 1798-1800. Although this piece is numbered as second in the Op. 18 set, it is generally believed to be the third in Beethoven’s chronological order of composition. He put off writing in the quartet form for a long time in his compositional life, and numerous sketches and revisions show that it was not an easy task for the young composer.

The second quartet, like all the others in the Op. 18 set, is comprised of four movements. It has earned the nickname “Compliments” because it is so polite and graceful in nature. The first movement is an Allegro that opens with a charming violin melody that leads to a quick cadence. Overall, this movement is pleasant, has many points of resolution (predictable cadences), and simple phrase structures. The melody, usually in the violin, is a combination of sweet lyric phrases and bright, playful fragments. During the lyrical parts the accompaniment is light and playful. It is easy to hear the influence of Haydn in the way Beethoven reuses and builds upon the opening melodic material throughout the movement. Even while heavily influenced by Haydn’s compositional methods, however, Beethoven adds his own delightful musical invention.

Adagio cantabile marks the character of the second movement, which begins with a melody that is sweet but also formal, almost courtly in nature. What makes this movement highly unusual is the subsequent Allegro section that boisterously interrupts halfway through. The allegro is as brief as it is unexpected, and the movement ends with the same adagio feel in which it began.

The third movement is, predictably, a light and playful Scherzo that dances along with the good nature of any Scherzo. Unlike many of Beethoven’s other Scherzos, however, this one does not contain any of the musical surprises that often bring a humorous or boisterous feel to the movement. It is, instead, lively but very polite in character.

The final movement is an Allegro with a Quasi Presto marking. It is quite energetic and quick from the start and, similarly to the first movement, the opening motif returns and is developed in many inventive ways. Most of the melodic motion is scalar, though it is combined with short lyrical melodies. The close of the movement is exuberant and in keeping with the good nature of the piece.

Before turning to the composition of string quartets, Beethoven devoted his first years in Vienna to mastering the genres popular in that city: piano sonatas, string trios, duo sonatas for piano and violin or cello, and short songs and opera arias. No doubt Beethoven’s apparent trepidation when approaching the string quartet medium was a result of the immense shadow cast by Haydn, whose Opp. 71 and 73 were composed in 1793, the year Beethoven began to study with the older master. Haydn published his six “Erdödy” Quartets, Op. 76, in 1797, and his two quartets of Opus 77 in 1799. To prepare himself for his eventual foray into the genre, Beethoven studied the works of others. In particular, he copied Haydn’s Opus 20/1 in 1793-1794, and Mozart’s K. 387 and 464 while he was beginning work on Op. 18 The quartets were published 1801 in Vienna, in two sets of three by Mollo & Co. They were not written in their published order, but rather Nos. 3, 1, 2, 5, 4, and 6.

The number of quartets comprising his Opus 18 is but one of Beethoven’s nods to tradition, for sets usually included six works. Also, in Nos. 2 and 5, Beethoven seems to confront his predecessors directly, and as a result, moves to another level of composition. In his Opus 18 quartets we find Beethoven both mastering the styles of his predecessors and forging into new territory. For instance, the independence of the four parts is much greater than in the works of his predecessors, which may be attributable to the fact that Beethoven developed his skills during a time freed from the hitherto ubiquitous basso continuo. Despite the numerous recent models, and despite the fact that the String Quartets, Op. 18, are clearly a product of their time, they could not have been written by any composer other than Beethoven. Dedicated to Prince Franz Joseph von Lobkowitz, the six quartets of Op. 18 constitute Beethoven’s most ambitious project of his early Vienna years.

The quartet in D major (No. 3) was the first composed. Its opening, with nearly all of the motion in the first violin supported by sustained harmonies, resembles the beginning of Haydn’s Quartet, Op. 50/6, also in D major. The first movement begins with an emphasis on the dominant-seventh chord, while the second theme group flirts with the minor dominant, allowing an unusual excursion into C major. The rest of the quartet comprises a conventional movement pattern, but the Presto finale is a sonata, not a rondo. Although it is not labeled as such, the third movement is a minuet, albeit with some unusual, forward-looking touches. For example, the return of the minuet after the trio is not the standard da capo repeat, but is completely written out, with additional repetitions of and variations on the original material.

The only quartet from Beethoven’s Opus 18 set to be cast in a minor key, this was also, despite its number, the last of the six to be completed. C minor would come to be a key Beethoven reserved for highly dramatic works, including most famously the Fifth Symphony. Before this quartet, though, he’d used C minor without any special sense of tragedy; now, for the first time, he invests his C minor music with a special emotional depth, particularly in the sonata form Allegro ma non tanto. This opening movement immediately spins forth a worried violin theme over agitated accompaniment, interrupted by a series of jagged chords. The violins continue with lyrical, minor mode material, still with a restless accompaniment in the viola and cello. The exposition continues through several brief episodes in the same vein, ending with an odd sequence of quiet chords, a soft allusion to the jagged chords heard earlier. In the development section, Beethoven heightens the anxiety through key modulations while essentially repeating the structure of the exposition; apparently he felt little need to wrench the thematic components apart and recombine their fragments. By the time the recapitulation arrives, the thematic pattern has been clarified.

The surprise comes with the structure of the inner movements. There’s no traditional slow movement; instead, Beethoven offers a scherzo followed by a minuet, both in moderate tempos. The scherzo is not the raucous joke Beethoven would favor in his symphonies. It feels more like a traditional minuet, with a fairly capricious character (the key is now C major). The structure could be considered a sonata form, with the central section being a largely polyphonic development of the themes Beethoven has already introduced.

The minuet proper, Allegretto, returns to C minor. If the scherzo seemed more like a minuet, this minuet has the character of a scherzo, fairly quick and unsettled. The trio features a jittery eighth note figure in the first violin, under which the second violin trades two-bar phrases with the viola and cello.

The concluding C minor Allegro is a rondo that begins with an impassioned theme dominated by the first violin. The second section is more placid, and the next contrasting episode features humorous triplets rising from the cello up through the ensemble. The third contrasting episode picks up more of the agitation of the rondo theme, so when the latter returns one last time it can make its full effect only if played, as Beethoven indicates, as quickly as possible.

Despite its numbering, this quartet was probably the fourth of the six that comprise Beethoven’s Opus 18 set, dedicated to Prince Lobkowitz. The composer reordered the entire group upon its completion in 1800. The musicologist Brandenburg claimed that the chronological order of the six works was 3, 1, 2, 5, 4, and 6. Beethoven’s rearranging was logical, based apparently on the character of the quartets. In general, the first three (in the final numbering) are fairly faithful to Classical forms, while the second three tend to be unorthodox and somewhat experimental. In certain respects, the latter trio of quartets might be viewed as a significant part of the composer’s transition to the methods and styles of his so-called middle period.

The String Quartet No. 5’s first movement, marked Allegro, opens with a theme that is more than vaguely Mozartean. But much of the music here is also reminiscent of parts of Beethoven’s own Sonata for Violin & Piano No. 2 in A major, Op. 12/2 (1797-1798), written in the same key. The main theme is joyous and the mood optimistic, though the second subject contains material that is a bit more serious. The development section is noteworthy for what it mostly lacks — development. Only the latter half contains substantive development, but in a manner that looks backward in style, or, rather, aims toward the simple. The recapitulation includes some delightful changes in the material.

The second-movement Menuetto features an attractive, lively dance theme whose simplicity is beguiling for its grace and subtle character. If the first movement stands as the least progressive panel in this work, then the trio of this Menuetto may be the most advanced. Yet, it too, is rather simple, and more than one commentator has heard in it a foreshadowing of the music of Schubert. Beethoven puts on display some interesting canonic writing when the main dance melody returns. The next movement is marked Andante cantabile, and its Mozartean character has often been noted. Mozart’s Quartet in A, K. 464, has been cited as the work Beethoven chose as a model, and the corresponding movements in that work divulge many similarities with the third and fourth movements here. Beethoven presents a simple slow theme and follows with five variations. As suggested above, the finale, too, is indebted to Mozart. Indeed, Beethoven borrows a theme, placing it near the end of the development section. But “imitation” would be too strong a word to use in describing the relationship between the two composers’ music in the finale. In fact, the main themes clearly come from the pen of Beethoven, and the development section, muscular and anxious, is also easily recognized as his, despite the thematic foray into Mozart’s world. This Allegro movement features a recapitulation and closes with an attractive coda.

A typical performance of the quartet lasts around a half hour.

This was the last of the group of six quartets in the Op. 18 set. While that might appear obvious in perusing the headnote, in actuality the numbers in this collection do not necessarily correspond to their order of composition since Beethoven reordered all six works after finishing them in 1800. The third actually appears to have been composed first. The reason the composer changed the order was apparently due to the character of the quartets: the first three generally adhere to traditional forms, while the latter group are fairly unorthodox and varied in style. But there may have been another reason he arranged them so: the last three all contain substantial references to the past, the Fourth and Fifth showing deference to Mozart and the Sixth appearing as a patchwork of compositions out of Beethoven’s own past. Still, both groups of quartets are worthwhile, and the Sixth especially, in its second and fourth movements, offers glimpses of the mature Beethoven.

The first movement is marked Allegro con brio, and while it hardly introduces anything innovative, it does present some musical merrymaking. The joyful main theme contains that already characteristic Beethovenian urgency. The second theme is less driven and takes on an almost stately character at the outset, but eventually turns effervescent and manic. The material is repeated, after which the development section ensues. Here, the music becomes a little more serious, even tense. There is a clever little joke that occurs in the latter part, when the music unexpectedly stops dead, suddenly capturing the attention of the listener. After the development concludes, the main material is heard again and the movement ends.

The second movement is an Adagio of great beauty and simplicity. Yet, as was so often the case with this composer, his simplicity has a sophistication. It comes across as pure music, clothed in instrumentation that is perfectly appropriate for its innocent character. The alternate melody is also simple and lovely. The main theme returns and there follows a brief coda. While this is the least sensational movement in the work, it may be the most effective.

The Scherzo ensues. Marked Allegro, it is a busy, talkative movement, full of joy and humor, and it presents such a contrast to the Adagio that one feels its playfulness and humor more strongly. The finale, subtitled “La Malinconia” and marked Adagio at the outset and later Allegretto quasi allegro, presents probably the most complex music in the work. It begins with a dark, slow introduction, quite unlike anything else in the quartet. The mood is mysterious and intense throughout the first third of the movement. When the Allegretto section begins, Beethoven does not take listeners back to the backward-looking delight of the first movement, but rather to a more modern sound of joy. The character of the themes is decidedly less rooted in the language of Mozart and Haydn here, more foretelling of Beethoven’s own style to come.

Fast Shipping and Professional Packing

Due to our longstanding partnership with UPS FedEx DHL and other leading international carriers, we are able to provide a range of shipping options. Our warehouse staff are highly trained to pack your goods exactly according to the specifications that we supply. Your goods will undergo a thorough examination and will be safely packaged prior to being sent out. Everyday we deliver hundreds of packages to our customers from all over the world. This is an indication of our dedication to being the largest online retailer worldwide. Warehouses and distribution centers can be located in Europe as well as the USA.

Orders with more than 1 item are assigned processing periods for each item.

Before shipment, all ordered products will be thoroughly inspected. Today, most orders will be shipped within 48 hours. The estimated delivery time is between 3-7 days.

Returns

The stock is constantly changing. It's not entirely managed by us since we are involved with multiple parties such as the factory and our storage. The actual stock can fluctuate at any time. Please understand it may happen that your order will be out of stock when the order is placed.

Our policy is valid for 30 days. If you haven't received your product within 30 days, we're not able to issue either a return or exchange.

You are able to return a product if it is unused and in the same condition when you received it. It must also still remain in the original packaging.

Related products

MUSIC CD

MUSIC CD

MUSIC CD