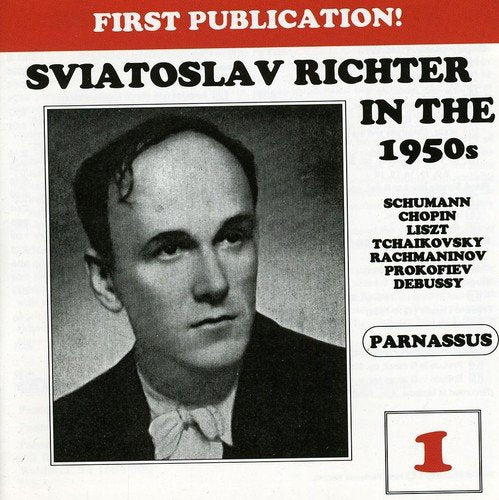

RICHTER IN THE 1950’S – VOLUME 1 (2 CD) PARNASSUS

$ 9,99 $ 5,99

Sviatoslav Richter in the 1950s, Vol. 1

Sviatoslav Richter (piano)

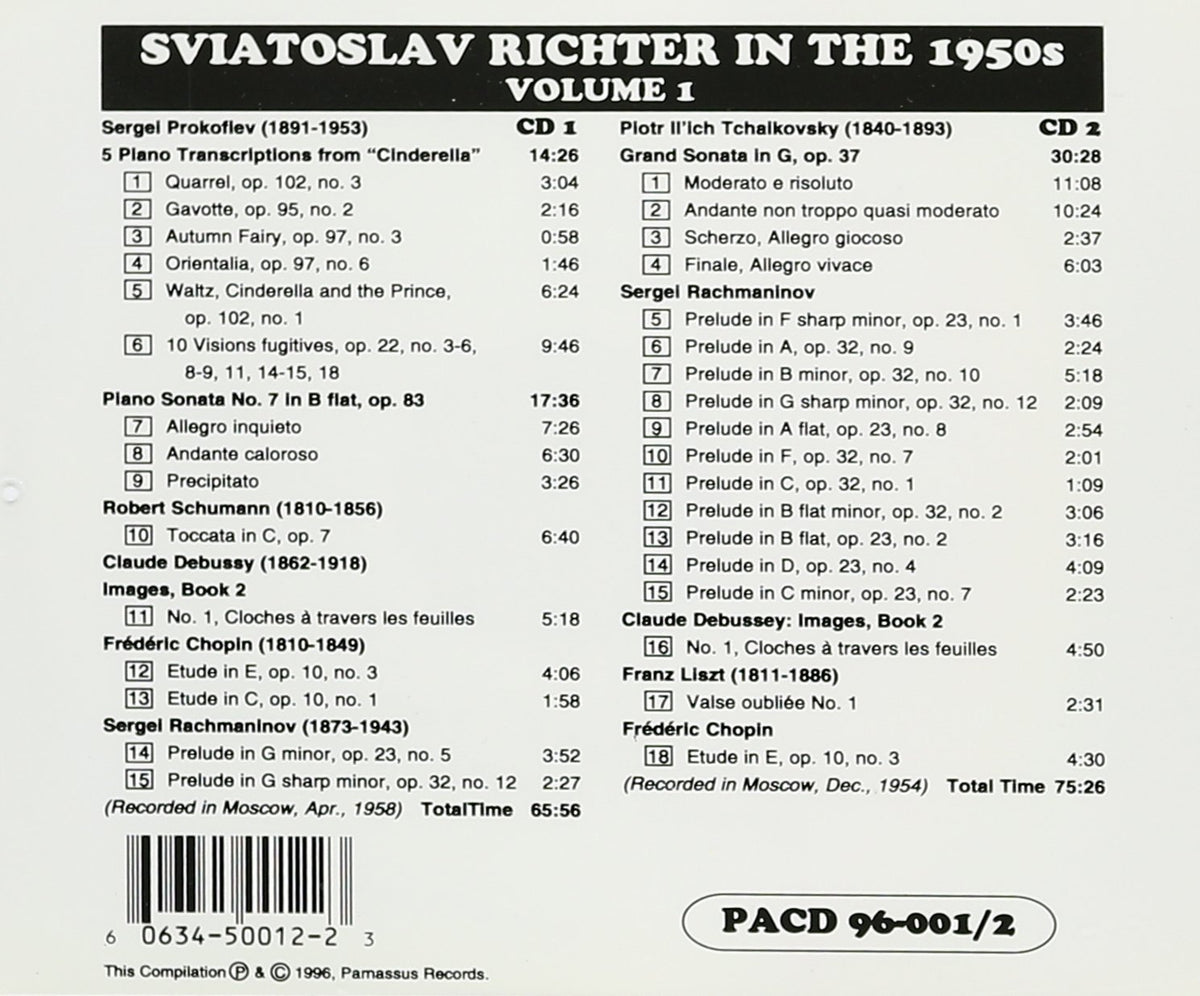

CD 1

Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953)

5 Piano Transcriptions from “Cindarella” 14:26

1) Quarrel, op. 102, no.3 3:04

2) Gavotte, op.95, no.2 2:16

3) Autumn Fairy, op.97, no.3 0:58

4) Waltz, Cinderella and the Prince op. 102, no. 1 6:24

5) 10 Visiones fugitives, op. 22, no. 3-6, 8-9, 11, 14-15 ,18 9:46

Piano Sonata No.7 in B flat, op. 83 17:36

7) Allegro inquieto 7:26

8) Andante caloroso 6:30

9) Precipitato 3:26

Robert Schumann (1810 – 1856)

10) Toccata in C, op. 7 6:40

Claude Debbusy (1862 – 1918)

Images Book 2

11) No.1, Cloches a travers les feuilles 5:18

Frederic Chopin (1810 – 1849)

12) Etude in E, op. 10, no. 3 4:06

13) Etude in C, op. 10, no. 1 1:58

Sergei Rachmaninov (1873 – 1943)

14) Prelude in G minor, op. 23, no. 5 3:52

15) Prelude in G sharp min, op.32, no.12 2:27

(Recorded in Moscow, April 1958) Total Time 65:56

CD 2

Piotr Il’Ich Tchaikovsky (1840 – 1893)

Grand Sonata in G, op. 37 30:28

1) Moderato e risoluto 11:08

2) Andante non troppo quasi moserato10:24

3) Schezo, Allegro giocoso 2:37

4) Finale, Allegro vivace 6:03

Sergei Rachmaninov

5) Prelude in F sharp minor, op. 23, no.13:46

6) Prelude in A, op. 32, no. 9 2:24

7) Prelude in B minor, op. 32, no.10 5:18

8) Prelude in G sharp minor, op.32, no. 12 2:09

9) Prelide in A flat, op.23, no.8 2:54

10)Prelude in F, op.32, no. 7 2:01

11)Prelude in C, op.32, no.1 1:09

12)Prelude in B flat minor,op.32, no.2 3:06

13)Prelude in B flat, op.23, no.2 3:16

14)Prelude in D, op.23, no.4 4:09

15)Prelude in C minor, op.23, no.7 2:23

Claude Debussy: Images, Book 2

16)No.1, Cloches a travers les feuilles 4:50

Franz Liszt (1811 – 1886)

17)Valse Oubliee No. 1 2:31

Frederic Chopin

18)Etude in E, op.10, no.3 4:30

(Recorded in Moscow, December, 1954)

Total Time 75:26

Older readers may remember the shock of discovery when the first of Sviatoslav Richter’s discs made their way to the West. Since his first US tour in 1960, of course, he has been a fixture in the American musical imagination (although not in our concert halls), and we have been able to sample a far wider selection of his art in vastly better sound than that afforded by those early LPs. Still, as Richard Taruskin reminded us in an eloquent appreciation (13:3, p. 244), the Richter of the 1950s and early 1960s was a substantially more febrile artist than the “courtly, white-mustnchioed elder statesman” he has become–snd it is therefore not just nostalgia that gives his early recordings their magnetic chraracter. BMG’s ten-disc celebration, reviewed in detail by Leslie Gerber in 19:3, resurrected a significant number of scorching early studio recordings. The five discs under review, although they retrace much of the some repertoire, document live performances, sometimes a bit sloppier than the studio versions, but often fueled by an even more impetuos spirit and reaching an even higher emotional temperature.

This is especially evident in the stunning, four-disc salvo from Gerber’s own Parnassus Records, which brings us five hours of new recordings, in surprisingly serviceable sound, that have apparently never been released before. The contents consist largely of early-Richter staples-but the high-contrast peformances are, without exception, knockouts. All of Richter’s interpretations demonstrate a staggering diversity of touch (note how his hard-bitten account of Rachmaninov’s op.32/7 melts away at the end) and an almost unerring rhythmic control, both of small gestures and of larger paragraphs–note, for instance, how the Chopin Etude, op. lO/I, explodes forth as a single utterance. But what marks Richter’s early virtuoso efforts in particular is the way these qualities combine to grip you, rather than persuade you. There are other Richter performances that are more lighthearted (for instance, his four-hand Mozart with Britten; see 16:1); there are others, like his early 80s Tokyo Prokofiev (17;3), that offer more density of detail; and there -are certainly others (most notably his contoversial Schubert Bb, 6:4; see Michael Ullman’s dissent in 14:4) that convey deeper philosophical insights. But his early performances have a demonic intensity that was often tempered in his later years; and these four discs offer ample opportunity to experience, undiluted, the aural adrenaline rush that Taruskin described.

Certainly, no one else manages to steer through the Schumann Toccata with such brio, largely because no one else, not even Horowitz, manages to shape the music’s syncopations so that the textures never clot. In part because of a quicker tcmpo, but also in part because of a greater sense of abandon, this fierce account of the finale of the Prokofiev Seventh is even mord overwhelming than his famous studio version. And despite moments of apparent brusqueness (patience is not in high supply on these discs), this 1953 dash through Pictures is so impulsive as to make his classic Sofia account seem almost blasé.

I don’t mean to suggest that these are relentlessly steely readings in the manner of Simon Barere. Richter has an astonishing capacity for elegance. too (try the sixth of the Prokofiev Visions) and his Rachmaninov, like the first movement of his Scriabin Second, can be extremely lush: try, for instance, the superb weighting of the cadences on op. 23/4. But when, for instance, he heightens the contrast of the first movement of the Tchaikovsky Sonata by sweetening up the second theme, he manages to do so without dissipating the sense of urgency–transforming, by sheer willpower, the music’s redundancy into propulsion. There are claws beneath the velvet passages in this chipper Tchaikovsky Concerto as well; and although his Scriabin Sixth and his Schumann Humoresque both manifest a remarkable sympathy for the music’s mercurial swings, there is an underlying edge to both works that is apt to keep you off balance. Given the extent to which the Parnassus repertoire duplicates that of recordings already in the catalog (more or less contemporaneous performances with a similar interpretive slant and superior sound), I will resist the temptation to promote these discs as the best introduction to Richter’s art of the 1950s: but Richter aficionados should find them an invaluable supplement to their collections. Highly recommended.

Peter J.Rabinowitz; Fanfare May/June 1997

| PERFORMER | RICHTER, SVIATOSLAV |

|---|

Fast Shipping and Professional Packing

Due to our longstanding partnership with UPS FedEx DHL and other leading international carriers, we are able to provide a range of shipping options. Our warehouse staff are highly trained to pack your goods exactly according to the specifications that we supply. Your goods will undergo a thorough examination and will be safely packaged prior to being sent out. Everyday we deliver hundreds of packages to our customers from all over the world. This is an indication of our dedication to being the largest online retailer worldwide. Warehouses and distribution centers can be located in Europe as well as the USA.

Orders with more than 1 item are assigned processing periods for each item.

Before shipment, all ordered products will be thoroughly inspected. Today, most orders will be shipped within 48 hours. The estimated delivery time is between 3-7 days.

Returns

The stock is constantly changing. It's not entirely managed by us since we are involved with multiple parties such as the factory and our storage. The actual stock can fluctuate at any time. Please understand it may happen that your order will be out of stock when the order is placed.

Our policy is valid for 30 days. If you haven't received your product within 30 days, we're not able to issue either a return or exchange.

You are able to return a product if it is unused and in the same condition when you received it. It must also still remain in the original packaging.